Introduction to Primary Sources

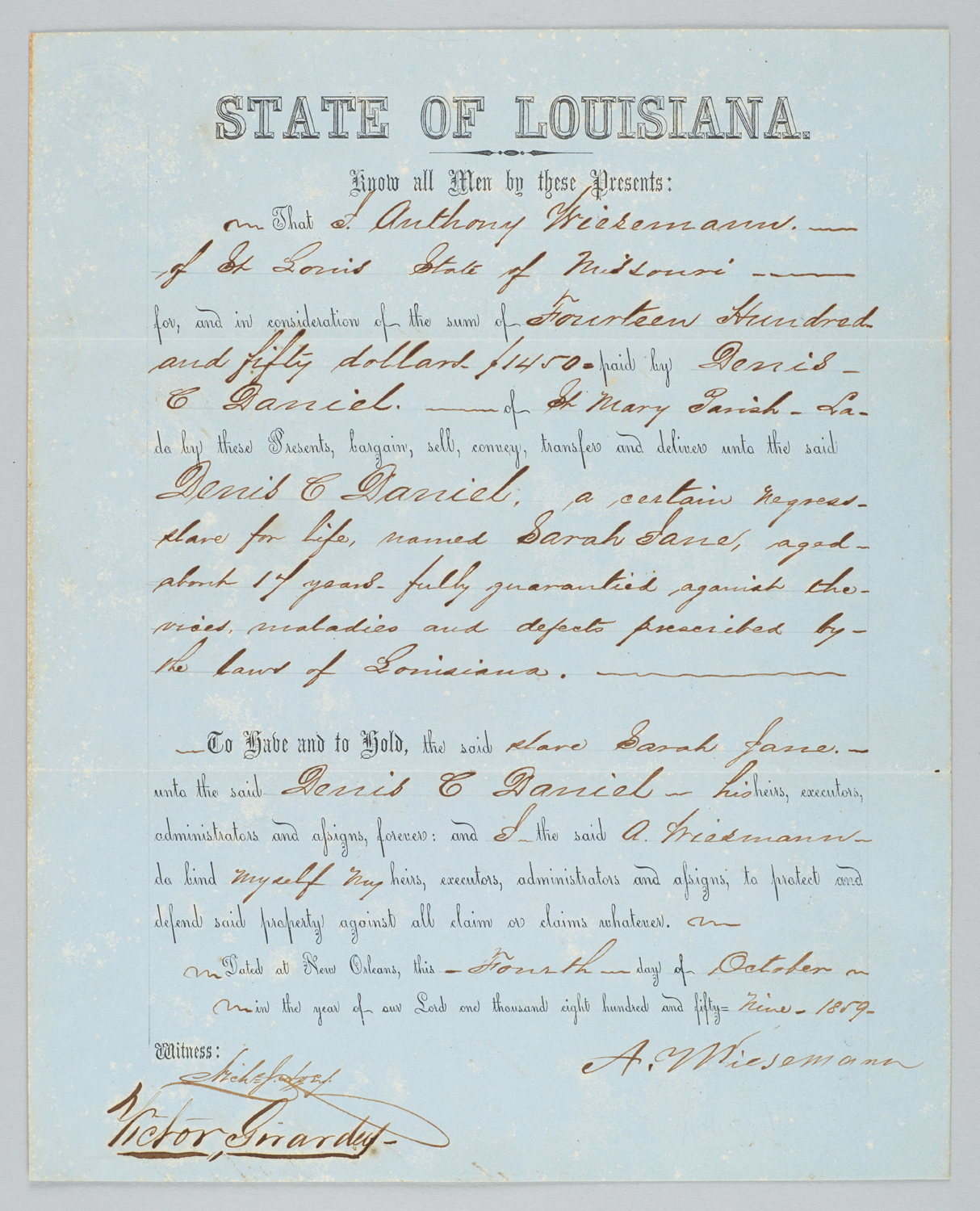

A bill of sale recording the purchase of a slave, desertion lists from a Confederate army regiment, writing manuals used by freedmen and women to achieve literacy – these and other primary sources will be featured and examined throughout the course. Selected from the collections of Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library, these materials will complement the lectures and discussion forums to enrich our understanding of the United States in the Era of Civil War and Reconstruction.

What is a primary source?

A primary source is a document, image, or artifact that provides first-hand or eyewitness information about a particular historical person, event, or idea. Typical examples of primary sources include letters, diaries, newspapers, photographs, paintings, maps, and oral histories. Historians can use primary sources to answer research questions and to gather evidence to support their arguments.

Working with primary sources

When working with primary sources it is important to begin with a few observational and interpretive questions, which can often suggest future research directions.

- When was this source created? If the source is not dated, can you use any contextual clues to make an educated guess?

- Who created it? If no individual’s name is apparent, can you guess their position within society?

- What was the original purpose of this source? Why was it created and what was its intent?

- Who is the intended audience of the source? How does this influence the way information is presented?

- Is there anyone, besides the author, who is represented in the source? What can you learn about them?

- How has the meaning of the source changed over time?

- How might a historian use this source as a piece of evidence? What research questions might it help to answer? What story might you tell using this source?

Sample Exercise

Using the questions above to examine this Bill of Sale from the State of Louisiana might elicit the following types of answers:

Section 1 Primary Sources

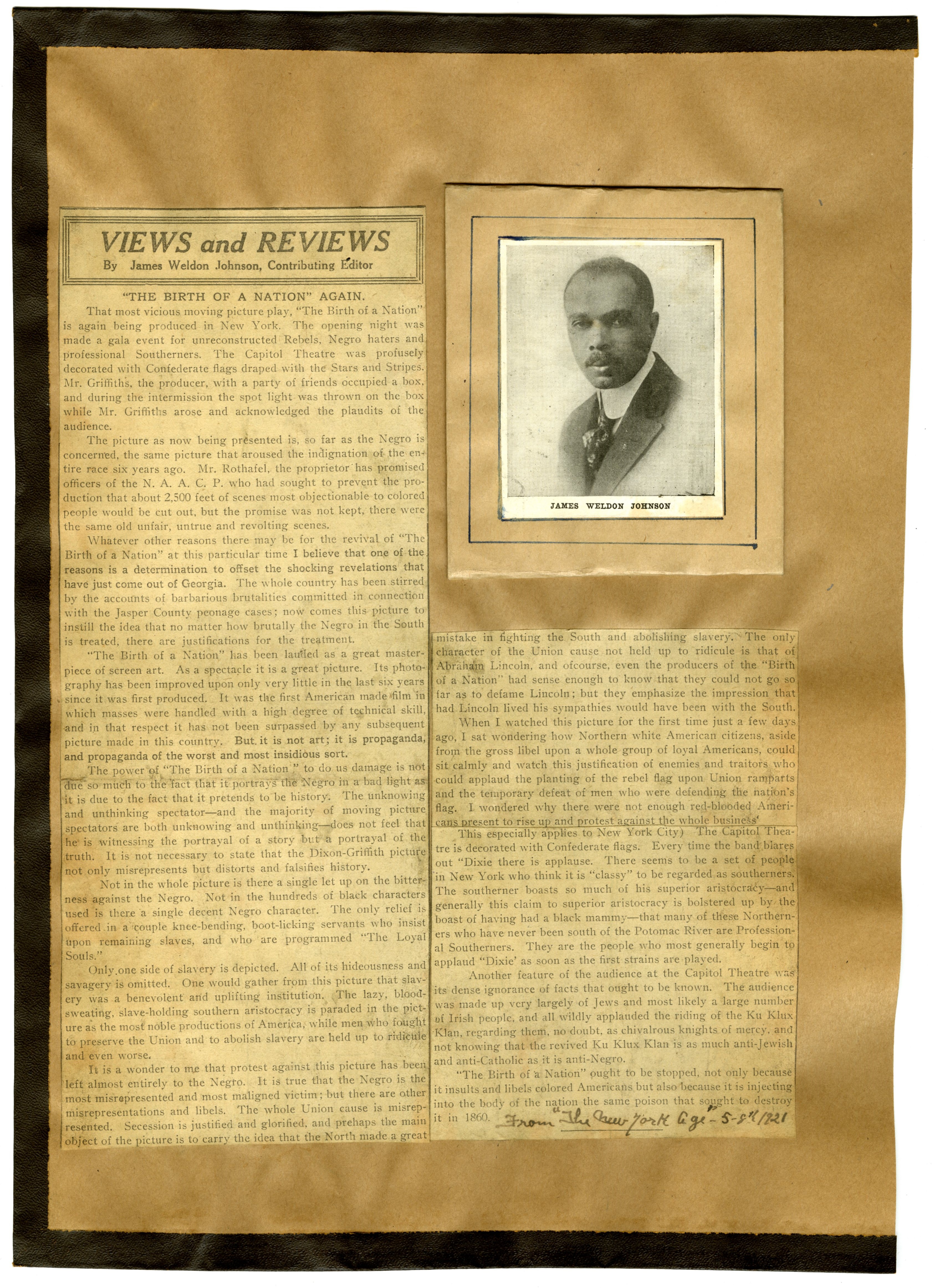

As Professor William Dunning and his protégés at Columbia University fashioned a scholarly narrative of Reconstruction that denigrated African Americans, novelists and filmmakers perpetuated similar mythologies for a wider public. The 1915 film The Birth of a Nation was adapted by D.W. Griffith from Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman. Professors and popularizers both operated in a complex historical moment shaped by Jim Crow laws in the South, mass-immigration in northern cities, the crisis of World War I, the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, and the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

The archival sources this week offer a glimpse into the passions stoked by this cultural and political moment. In 1921, five years after its initial release, Birth of a Nation appeared again in theaters. Newspaper clippings and an original ink drawing from the papers of L.S. Alexander Gumby, a Harlem historian and archivist, hint at the complex response with which New Yorkers greeted the film’s reprise.

Examine the documents. If you haven’t done so already, please consult the “Primary Sources” menu tab to familiarize yourself with the methods historians use to approach archival sources. Then examine the sources below and consider the analytical questions that follow.

|

| Click to Examine This week’s primary sources come from scrapbooks dedicated to African-American history. This page features an editorial entitled “‘Birth of a Nation’ Again,” published in the New York Age on May 8, 1921. Written by James Weldon Johnson, the executive director of the N.A.A.C.P., the article provides striking details about the legacy of Reconstruction. Source: Alexander Gumby Collection of Negroiana, RBML, Columbia University. |

|

| Click to Examine On this page of the scrapbook, Alexander Gumby pasted multiple items, including several newspaper clippings, a photograph, and an original playbill from the Capitol Theatre, the venue for The Birth of a Nation. Gumby’s scrapbooks – more than 150 in all – were a significant early attempt to preserve African-American stories. Gumby himself suggested the collection could well be called, “The Unwritten History,” since white historians gave scant unbiased attention to the subject. In their day, the scrapbooks garnered widespread notice, touring the East Coast and attracting large audiences. |

|

| Click to Examine The final source this week is a graphic pen-and-ink sketch – also from the Gumby scrapbooks – depicting the controversy over The Birth of a Nation. |

Questions

- These sources describe the response in a twentieth century northern city to a film set in the South during the Civil War. They vividly show the importance of the past for the politics of the 1920s. In what ways can you find people in these sources using history to bolster and justify their actions, beliefs, and positions? What can you learn from these about racism in the North in the 1920s?

- What do these sources tell you about the interaction between historical scholarship, amateur history, and popular culture regarding the subjects of the Civil War and Reconstruction? Can you draw parallels to modern-day representations of these subjects in film, television, and other forms of mass media? (How does popular culture reflect changing interpretations of historical events?)

- One of the major themes of Birth of a Nation is a racist depiction of black men as sexual predators targeting white women. How do these newspaper articles contradict these racist notions of black masculinity? In the Times article about black ex-servicemen, what role do black women play in protesting the film?

Section 2 Primary Sources

|

| Click to Examine “Leaving Charleston on the City Being Bombarded,” image from J.T. Trowbridge, A Picture of the Desolated States, 1865-1868 (Hartford, Conn.: L. Stebbins, 1868). |

Charlestown, South Carolina, was a key Confederate port throughout the Civil War. Despite frequent Union attacks – including two years of sustained artillery assault – the city did not fall until February 18, 1865. As Confederate troops retreated, burning cotton and military stores in their wake, they left chaos behind them – as the above illustration shows. While most of the city’s wealthy residents had already fled, Charleston was still inhabited by thousands of impoverished people, including white women and children from neighboring communities who sought shelter in the city, Confederate deserters, and former slaves. As the war came to a close, the Union forces that occupied Charleston confronted the problem of protecting and provisioning these survivors.

African Americans – free and freed – seized the opportunity to assert their political voice. Conveying a series of resolutions adopted “at a meeting of the colored citizens of Charleston, So.Ca.” on March 29, 1865, the document below combines expressions of gratitude with subtle claims to recognition and rights. Created a little over a month after the Union army took control of the city, and just days before General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, it shows the rapidity of change in this crucial historical moment. Examine the resolutions and answer the questions that follow (a typed transcript is provided):

- Examine the document for key words. Which two or three words do you think carry the most significance for the authors of these resolutions. Why?

- Why was it important for former slaves and other free people of color in Charleston to create a document like this one? Who was the audience for these resolutions?

- How do the composers of this document portray themselves? What clues can you find in the resolutions about how former slaves claimed their freedom in the aftermath of the Civil War?

|

| Click to Examine Resolutions adopted by a meeting of the colored citizens of Charleston, South Carolina, March 29, 1865. Alexander Gumby Collection of Negroiana, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. |

Transcript:

At a meeting of the colored citizens of Charleston, So.Ca. held at Zion’s Presbyterian church March 29th 1865 the following preamble and resolutions was unanimously adopted.

Whereas it is fitting that an expression should be given to the sentiments of deep seated grattitude that pervade our breasts, be it.

Resolved 1st That by the timely arrival of the army of the U.S. of A. in the city of Charleston on the 18th Feb. 1865, Our city was saved from a vast conflagration, Our homes from Devastation, and our persons from those indignities, that they would have been subjected to.

Resolved 2d that our thanks are due and are hereby freely tendered to the District Commander Brig. Gen. Hatch, and through him, to the Officers and Soldiers under his command, for the protection that they have so readily and so impartialy, bestowed since their occupation of this city.

Resolved 3d That to Admiral Dahlgreen U.S.N. we do hereby return our most sincere thanks, for the noble manner in which he cared for and administered to the wants our people at Georgetown, So.Ca. and be he assured that the same shall ever be held in grateful remembrance by us.

Resolved 4th That to His Excellency (the President of the U.S. of A. Abraham Lincoln) we return our most sincere thanks and never dying gratitude, for the noble and patriotic manner in which he promulgated the doctrines of Republicanism, and for his consistency in not only promising but invariably conforming his actions thereto and we shall ever be pleased to acknowledge and hail him as the champion of the rights of freemen.

Resolved 5th That a copy of these resolutions be transmitted to Brig. Gen. Hatch, Admiral Dahlgreen, His excellency the President of the U.S. of A. an that they be published in the Charleston courier.

Moses B. Camplin - Chairman

Robert C. De Large Secretary

Section 3 Primary Sources

After Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency and took on the task of Reconstruction. While Johnson initially appeared to take a hard stance towards Confederate leaders and wealthy planters, his policies soon proved to be too lenient, requiring only a bare minimum of change in the reconstructed Southern states. Johnson’s policies roused vehement opposition from Northern Radical Republicans. However, the Republican Party was still divided between these Radicals and more moderate Republicans who hoped to work with Johnson

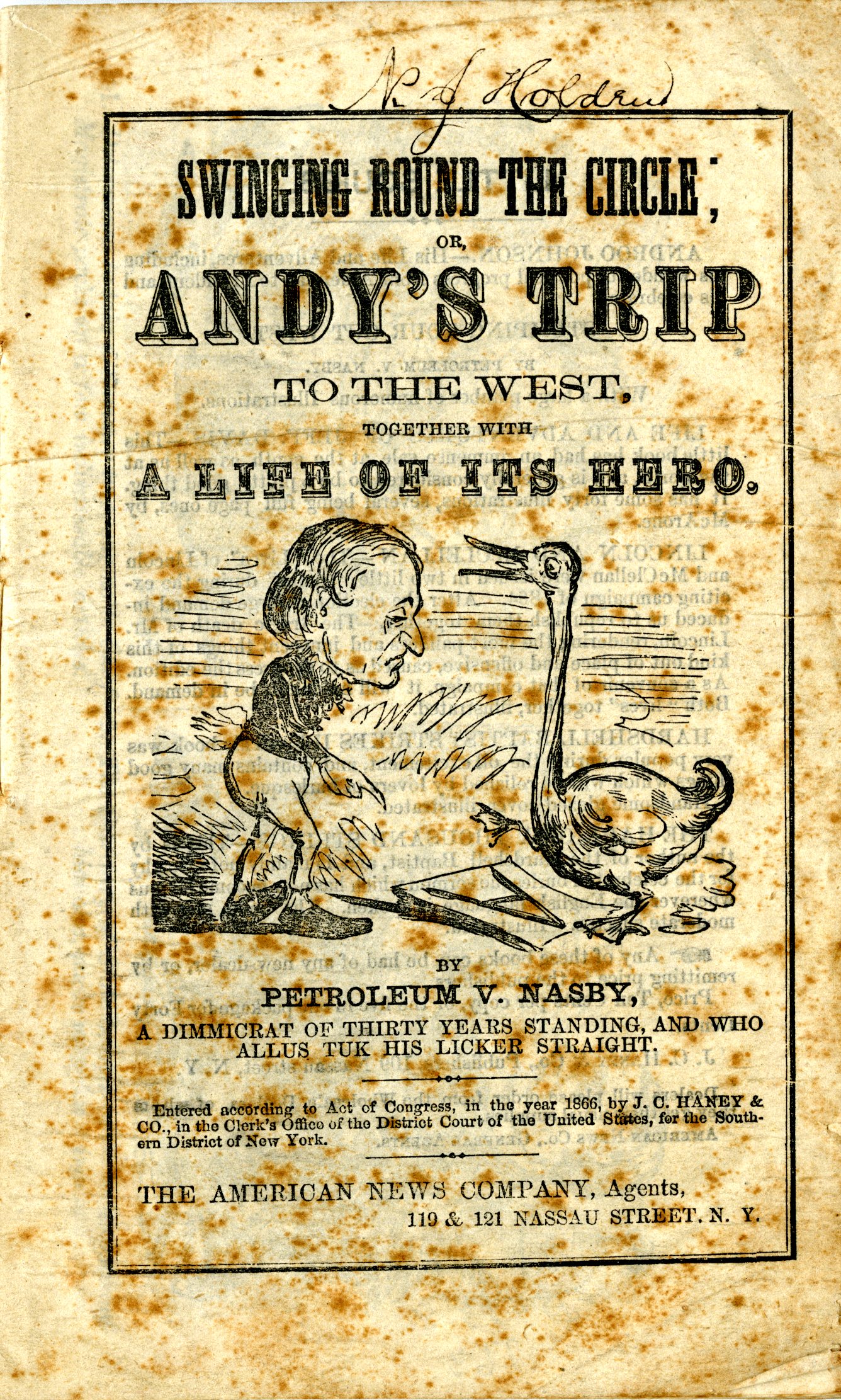

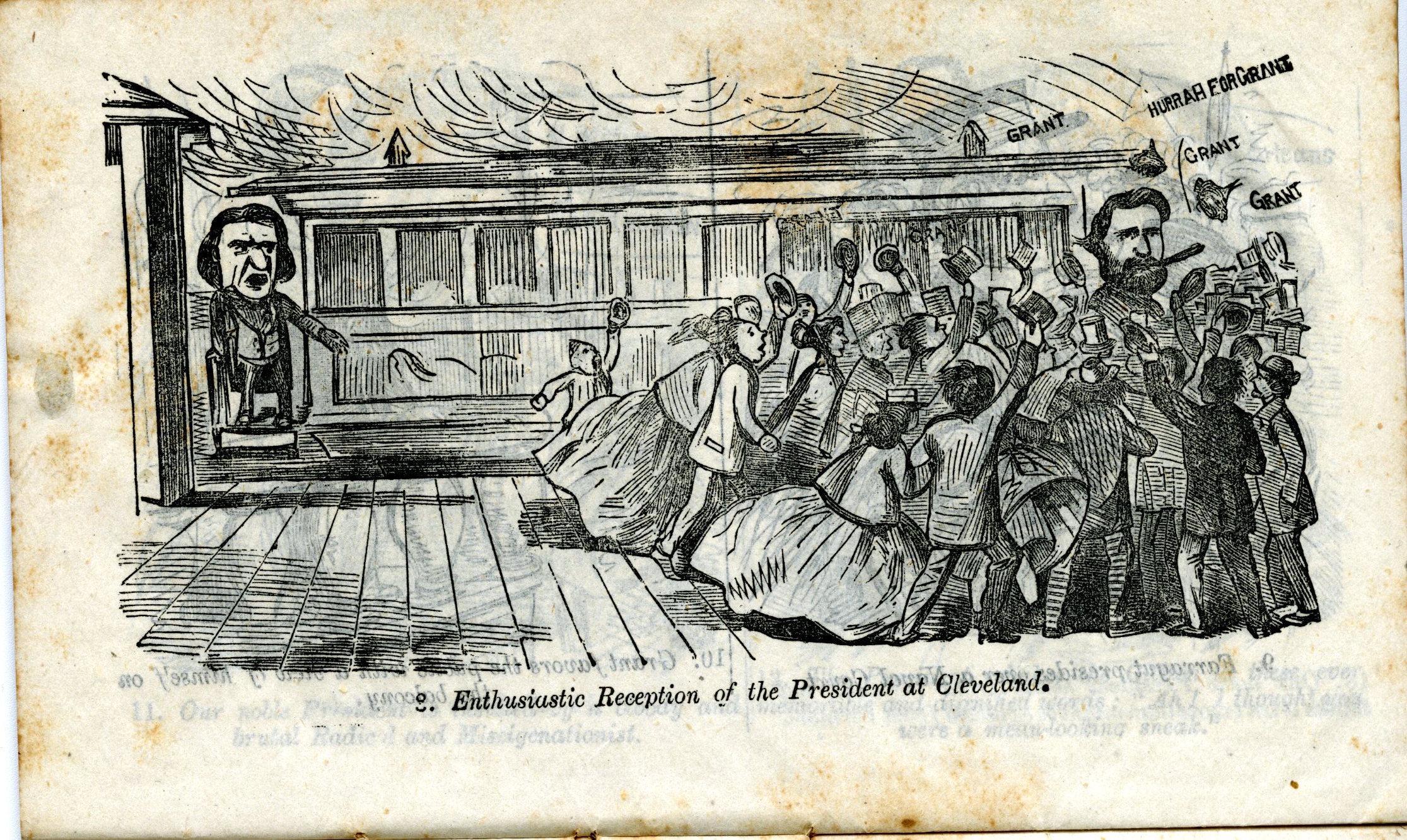

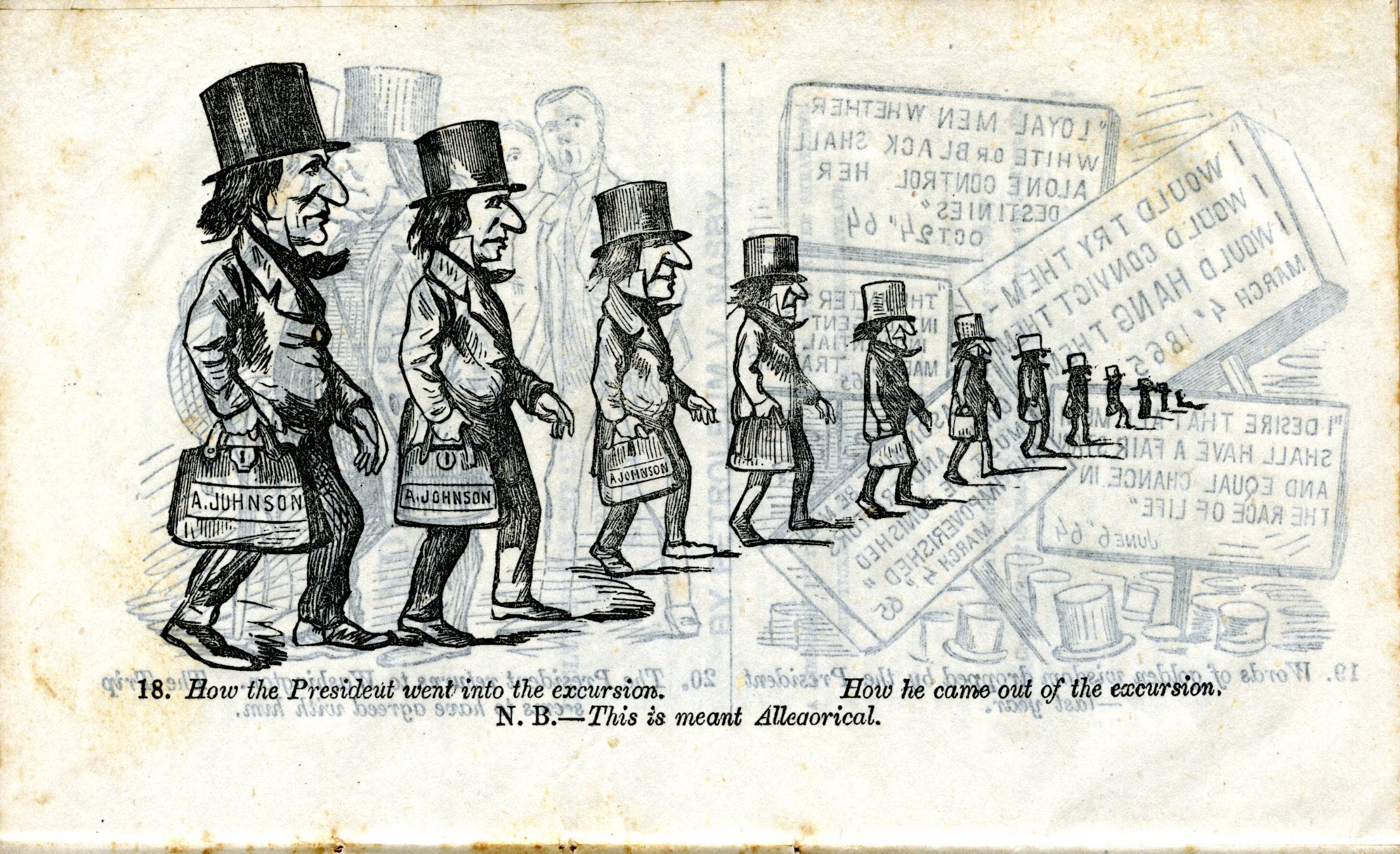

1866 was a pivotal year for Johnson and for the Republican Party. Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull proposed two Reconstruction bills: the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the Civil Rights Bill. Johnson vetoed both bills, reflecting both his rejection of the centralized power of the federal government and his deep racism. A chasm opened between Johnson and Congress. The Republicans rallied around the Fourteenth Amendment, while Johnson embarked on a speaking tour of the North in preparation for the congressional elections. This “swing around the circle,” in which Johnson promoted his Reconstruction plan by leveling wild accusations at Radical Republicans, garnered criticism and ridicule and paved the way for Radical Reconstruction.

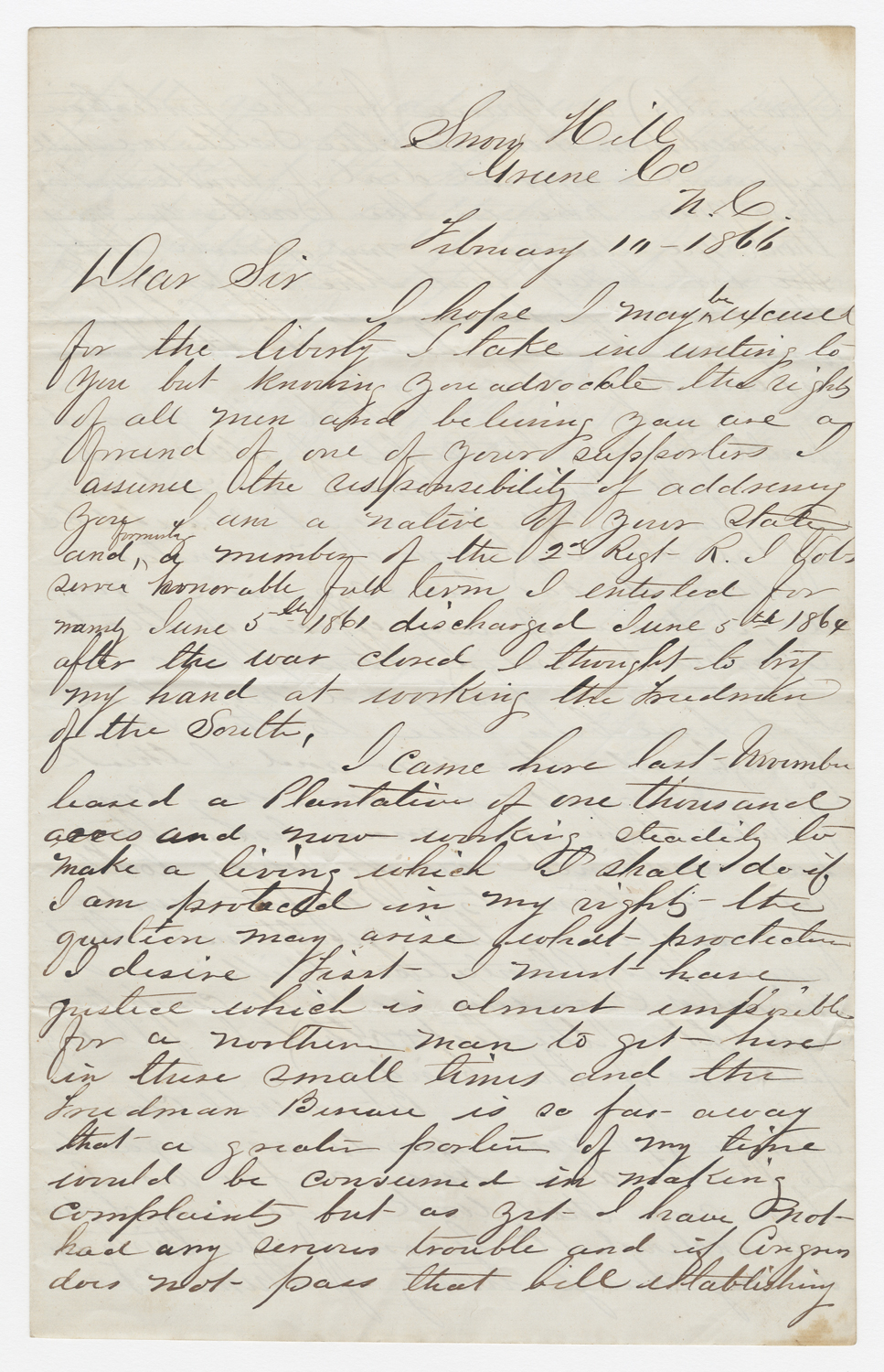

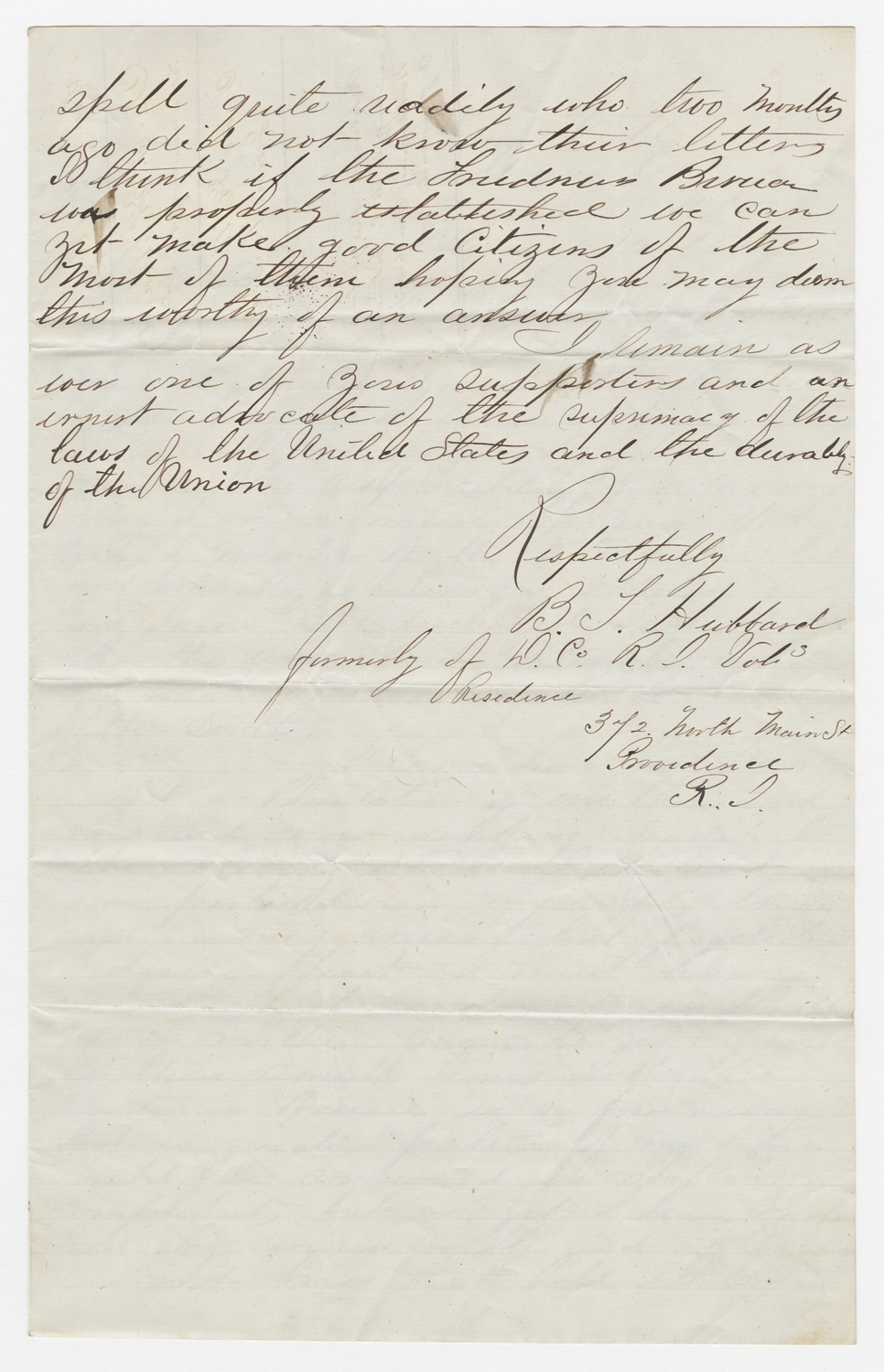

This week’s primary source documents chronicle the events of 1866 from varying perspectives. First, there are images taken from a pamphlet created by the satirical journalist David Ross Locke (writing under the pseudonym Petroleum V. Nasby) documenting Johnson’s disastrous “swing around the circle.” Secondly, we will examine a letter (with accompanying transcript) written by a former Union soldier, Benjamin T. Hubbard, from Rhode Island who took over the management of a plantation in North Carolina after the war. Hubbard wrote to his Rhode Island congressman, Senator William Sprague, asking him to support the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, just days before Johnson vetoed the measure.

|

|

Click to Examine |

|

|

Click to Examine |

|

|

Click to Examine |

Click to Examine |

Click to Examine |

| B[enjamin] T. Hubbard, Letter to [Senator] William Sprague, Snow Hill, Greene County, North Carolina, February 1866. From the William Sprague Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. | |

|

| Click to Examine B[enjamin] T. Hubbard, Letter to [Senator] William Sprague, Snow Hill, Greene County, North Carolina, February 1866. From the William Sprague Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. |

Transcript:

Snow Hill

Greene Co

N.C.

February 10, 1866

Dear Sir

I hope I may be excused for the liberty I take in writing to you but knowing you advocate the rights of all men and believing you are a friend of one of your supporters I assume the responsibility of addressing you I am a native of your state and formerly a member of the 2d Regt R.I Vols served honorable full term I enlisted for [???] June 5th 1861 discharged June 5th 1864 after the war closed I thought to try my hand at working the Freedmen of the South.

I came here last November leased a Plantation of one thousand acres and now working steadily to make a living which I shall do if I am protected in my rights – the questions may arise of what protections I desire First I must have justice which is almost impossible for a northern man to get here in these small times and the Freedman Bureau is so far away that a greater portion of my time would be consumed in making complaints but as yet I have not had any serious trouble and if Congress does not pass that bill establishing (permintly) a Bureau for the protection of Freedmen here in the South we shall experiance a great deal of trouble working these men here in the South you may think me strange in my opinion but I say that the majority of those men who were in the Confederate army are to day hostile to the Yankees as ever they were.

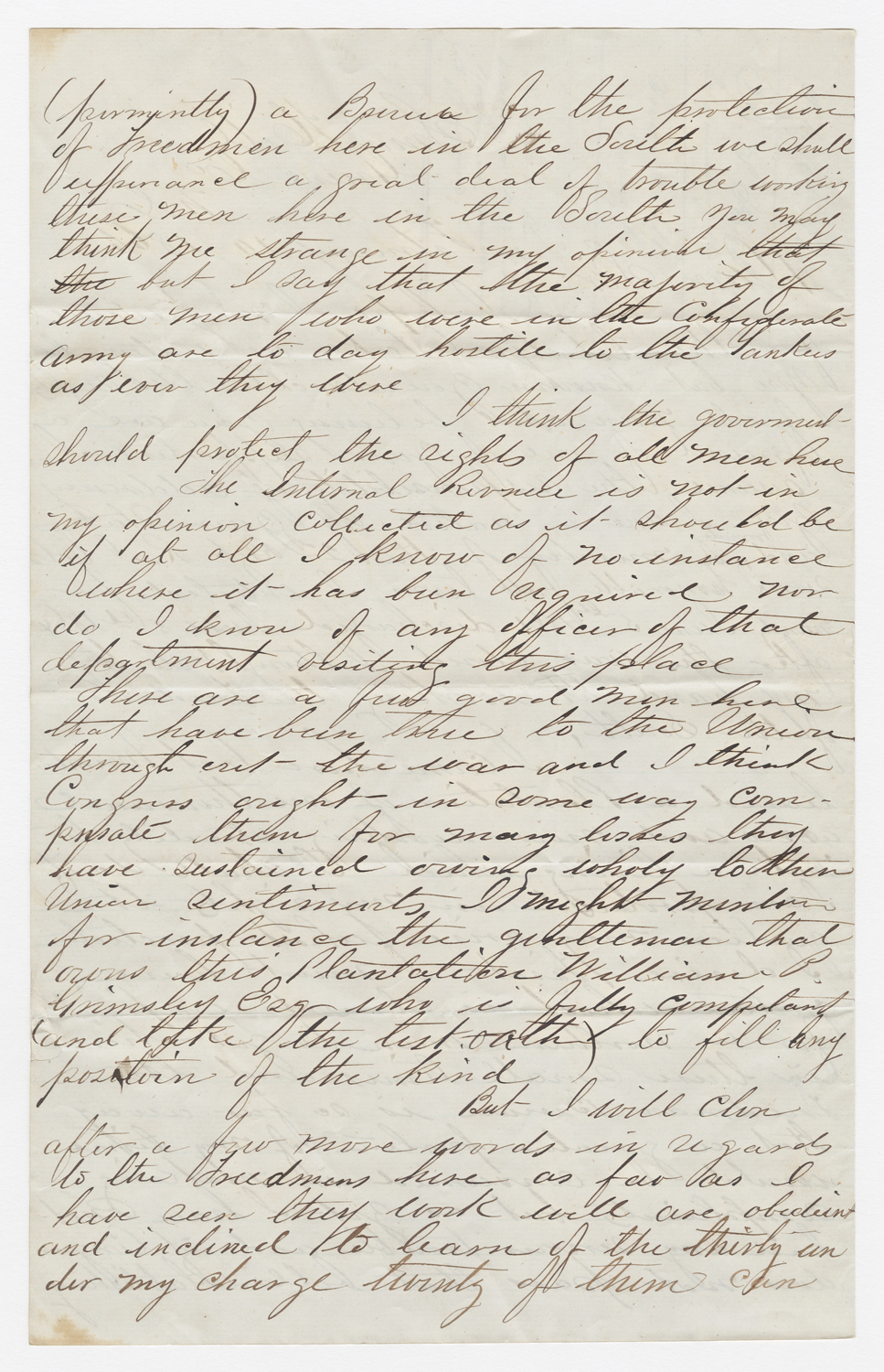

I think the goverment should protect the rights of all men here The Internal Revnue is not in my opinion collected as it should be if at all I know of no instance where it has been required nor do I know of any officer of that department visiting this place There are a few good men here that have been true to the Union through out the war and I think Congress ought in some way compensate them for many losses they have sustained owing wholy to their Union sentiments I might mention for instance the gentleman that owns this Plantation William P. Grimsley Esq who is fully competent (and take the test oath) to fill any position of the kind.

But I will close after a few more words in regards to the Freedmens here as far as I have seen they work well are obedient and inclined to learn of the thirty under my charge twenty of them can spell quite reddily who two months ago did not know their letters I think if the Freedmans Bureau was properly established we can yet make good Citizens of the most of them hoping you may deem this worthy of an answer

I remain as ever one of your supporters and an urgent advocate of the supremacy of the laws of the United States and the durability of the Union

Respectfully

B[enjamin] T. Hubbard

Formerly of D. Co. R. I. Vols

Resedence

372 North Main St.

Providence

R.I.

Questions

Examine the documents carefully, and then consider the following questions:

- Locke’s “Swinging Round the Circle” pamphlet exploits various unflattering stereotypes of Johnson and the Democratic Party. What aspects of Johnson’s background and his politics does Locke use to satirize his speaking tour?

- According to Hubbard’s letter, why was it important for the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau to be extended? Who are the various people and groups represented in this letter and what are their interests in supporting the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill?

- Both of these documents are examples of political commentary relating to Johnson and the events of 1866. Looking at them together, what conclusions can you draw from them about the political climate in the North and/or in the South during Presidential Reconstruction?

Section 4 Primary Sources

The Fifteenth Amendment, passed by Congress in February 1869, was the capstone on Reconstruction efforts to grant the rights of citizenship to black Americans living in the South as well as the North. This amendment declared, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall note be denied or abridged by the United States or by any other State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The suffrage amendment did not pass without opposition, however. The Democratic Party argued that former slaves were undeserving of suffrage rights, and women’s rights advocates also opposed the amendment, arguing that it did not go far enough to promote freedom and equality for all. Feminist leaders, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, split with their former allies among abolitionists and Radical Republicans to repudiate the amendment. They argued that native-born white women faced bondage as subordinates to white men and therefore deserved enfranchisement as much as, or even more than, black men and immigrants.

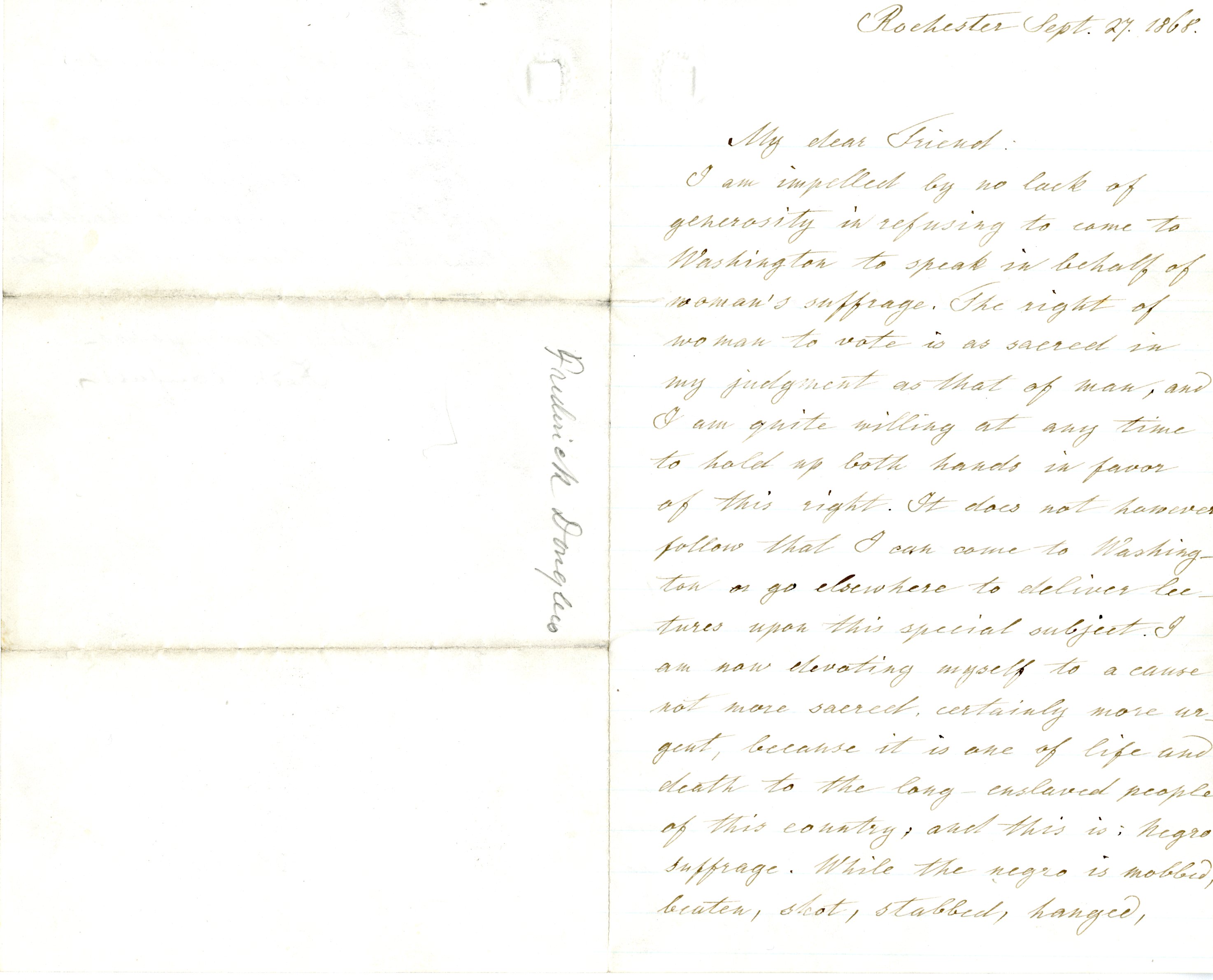

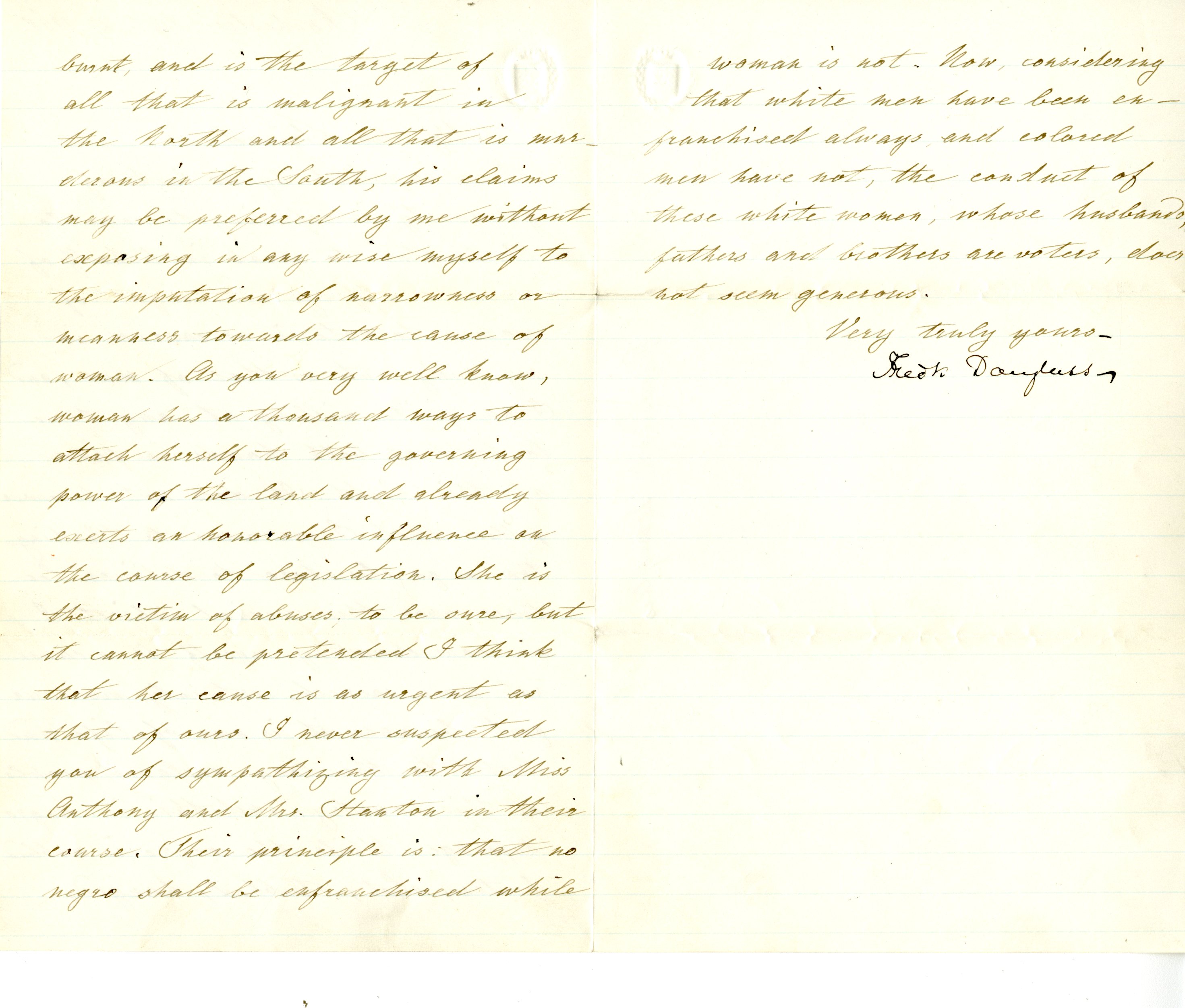

The primary source document for this week offers interesting insight into the debates occurring between feminists and abolitionists over the question of universal suffrage. Dated September 27, 1868, this letter was written by Frederick Douglass, a prominent black abolitionist best known for his autobiographies documenting his experiences as a slave and escape from bondage. He addresses Josephine S.W. Griffing, an abolitionist and women’s rights activist allied with Stanton and Anthony in their crusade for women’s suffrage. In this letter, Douglass articulates his reasoning for prioritizing suffrage for black men over the enfranchisement of white women.

Click to Examine |

Click to Examine |

| Letter from Frederick Douglass, Rochester, 27 February 1868, to Josephine S. W. Griffing. Josephine W. Griffing Letters, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. | |

Transcript

Rochester Sept. 27, 1868

My dear Friend:

I am impelled by no lack of generosity in refusing to come to Washington to speak in behalf of woman’s suffrage. The right of woman to vote is as sacred in my judgment as that of man, and I am quite willing at any time to hold up both hands in favor of this right. It does not however follow that I can come to Washington or go elsewhere to deliver lectures upon this special subject. I am now elevating myself to a cause not more sacred, certainly more urgent, because it is one of life and death to the long-enslaved people of this country; and this is: Negro suffrage. While the negro is mobbed, beaten, shot, stabbed, hanged, burnt, and is the target of all that is malignant in the North and all that is murderous in the South, his claims may be preferred by me without exposing an any wise myself to the imputation of narrowness or meanness towards the cause of woman. As you very well know, woman has a thousand ways to attach herself to the governing power of the land and already exerts an honorable influence on the course of legislation. She is the victim of abuses, to be sure, but it cannot be pretended I think that her cause is as urgent as that of ours. I never suspected you of sympathizing with Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton in their course. Their principle is that no negro shall be enfranchised while woman is not. Now, considering that white men have been enfranchised always and colored men have not, the conduct of these white women, whose husbands, fathers and brothers are voters, does not seem generous.

Very truly yours,

Fredk. Douglass

Questions

Read the letter closely (a transcript follows the images), and consider the following questions:

- Examine the document for key words. What word or words do you think are especially significant to Douglass’s argument? Why?

- How does this document expose some of the limitations of freedom in the Reconstruction-era United States?

- While Douglass mentions black men, white men, and white women in relation to voting rights, he does not mention black women. How might the inclusion of black women change the terms of this discussion?

Section 5 Primary Sources: “Black Reconstruction” and Black Political Leaders

|

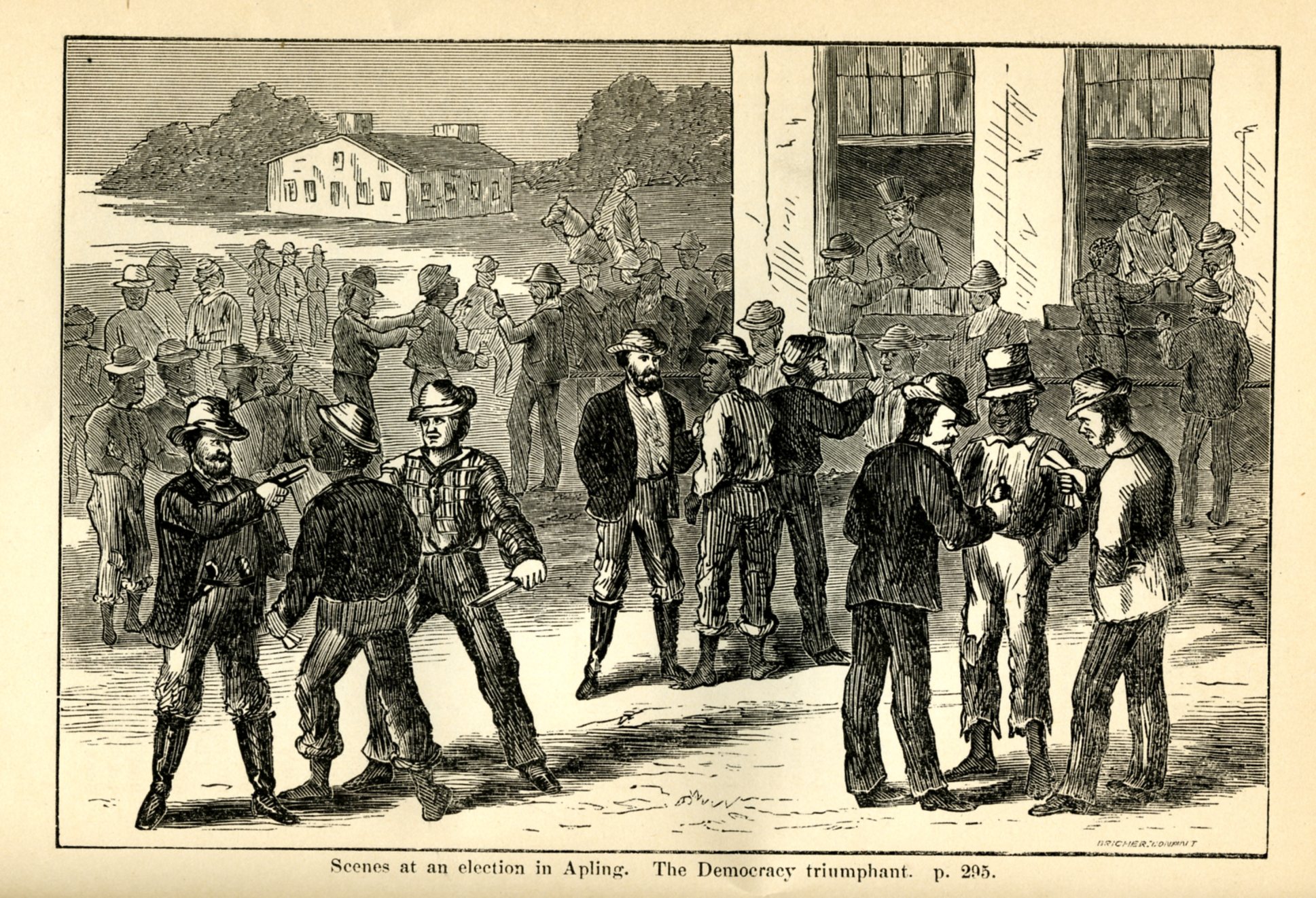

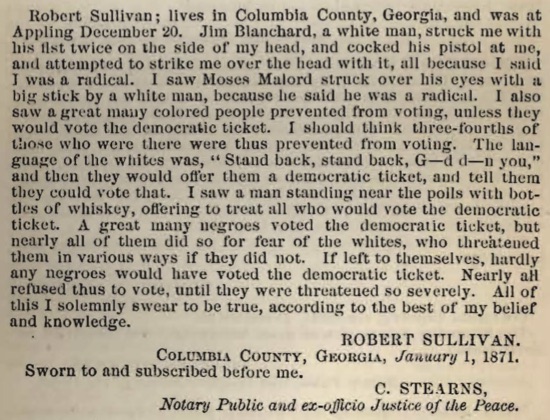

| Click to Examine "Scenes at an election in Ap[p]ling. The Democracy triumphant." From Charles Stearns, The Black Man of the South, and the Rebels, or, the Characteristics of the Former, and the Recent Outrages of the Latter, New York: American News Co., 1872. |

With the Reconstruction Act of 1867 and later the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, black men in the South were able to participate in electoral politics for the first time. Black voters fueled the success of the Republican Party in the South, and black men were elected to county, state, and federal offices. While these Republican governments encountered obstacles at every turn, they took significant steps in the arenas of civil rights legislation, education, and economic reform.

In spite of the accomplishments of these Republican governments, Southern opponents of Reconstruction, including planters, merchants, and Democratic politicians, painted them as corrupt and decried the rise of “black supremacy.” The charges of these opponents became cemented in the popular historical memory of the Reconstruction era, depicting African Americans’ entry into politics as chaotic and corrupt. Primary sources from the period, however, reveal a different history. They show how black Americans struggled to claim their political rights with dignity, even as they faced racism and the threat of violent reprisals from white Democrats.

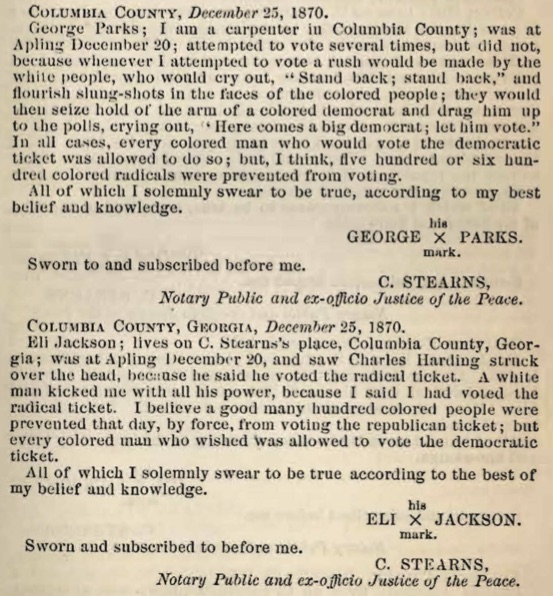

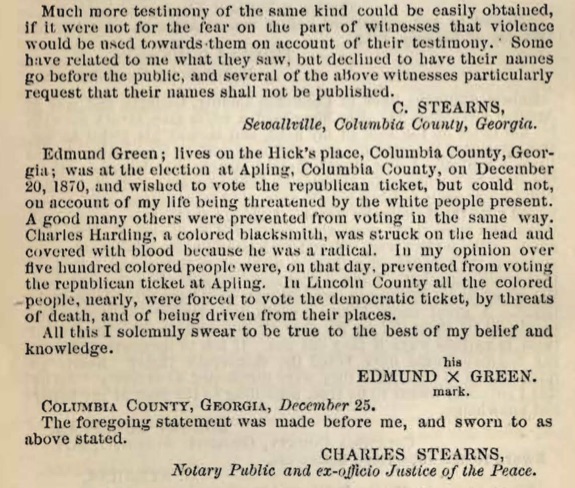

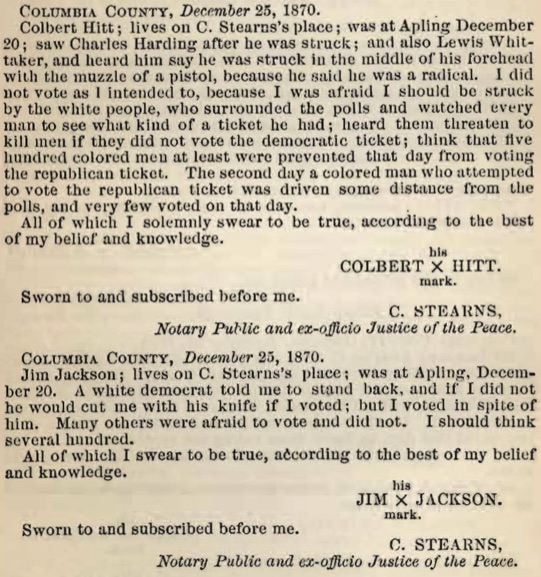

This week’s primary sources document the emergence of black politics in the South during Reconstruction from different perspectives. The image above and the text below are drawn from Charles Stearns’s book The Black Man of the South and the Rebels. Stearns was a Northerner and a Republican who moved to Georgia during Reconstruction and set up a plantation based on free labor. His book describes his experiences, paying close attention to political and social tensions between former slaves and white Southerners. The image above and the excerpted texts below depict an 1870 election in Appling, Georgia in which white Democrats secured victory largely by terrorizing black Republican voters. The scrapbook pages have clippings from Harper’s Weekly depicting black politicians elected during Reconstruction. Examine these primary sources carefully, and then consider the interpretive questions that follow.

Click to Examine |

Click to Examine |

| Testimony from Charles Stearns, The Black Man of the South, and the Rebels, or, the Characteristics of the Former, and the Recent Outrages of the Latter, New York: American News Co., 1872. | |

Click to Examine |

Click to Examine |

| Testimony from Charles Stearns, The Black Man of the South, and the Rebels, or, the Characteristics of the Former, and the Recent Outrages of the Latter, New York: American News Co., 1872. | |

|

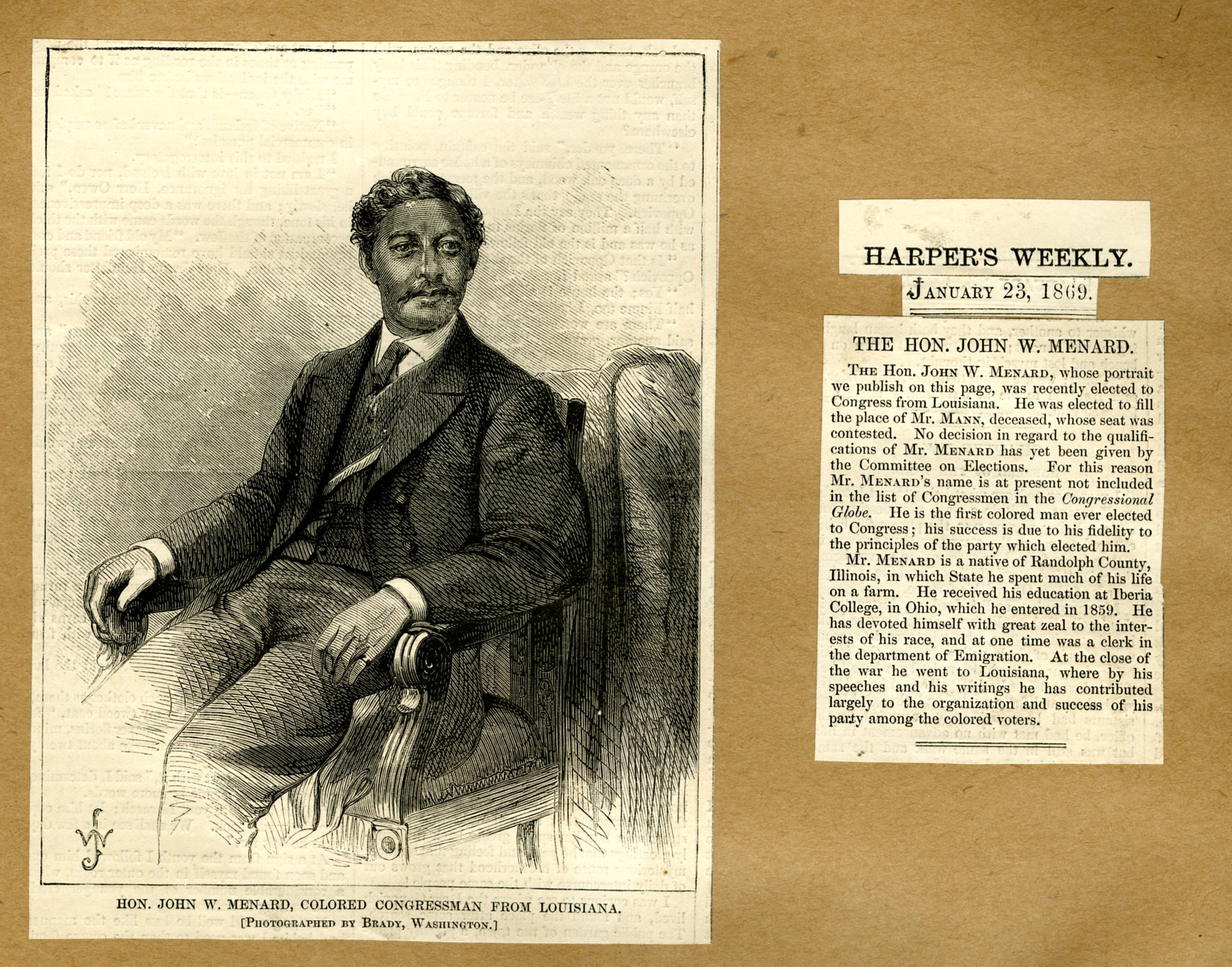

| Click to Examine John W. Menard, Louisiana Congressman, 1869. From “Negro in Politics” Scrapbook, Alexander Gumby Collection of Negroiana, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. |

|

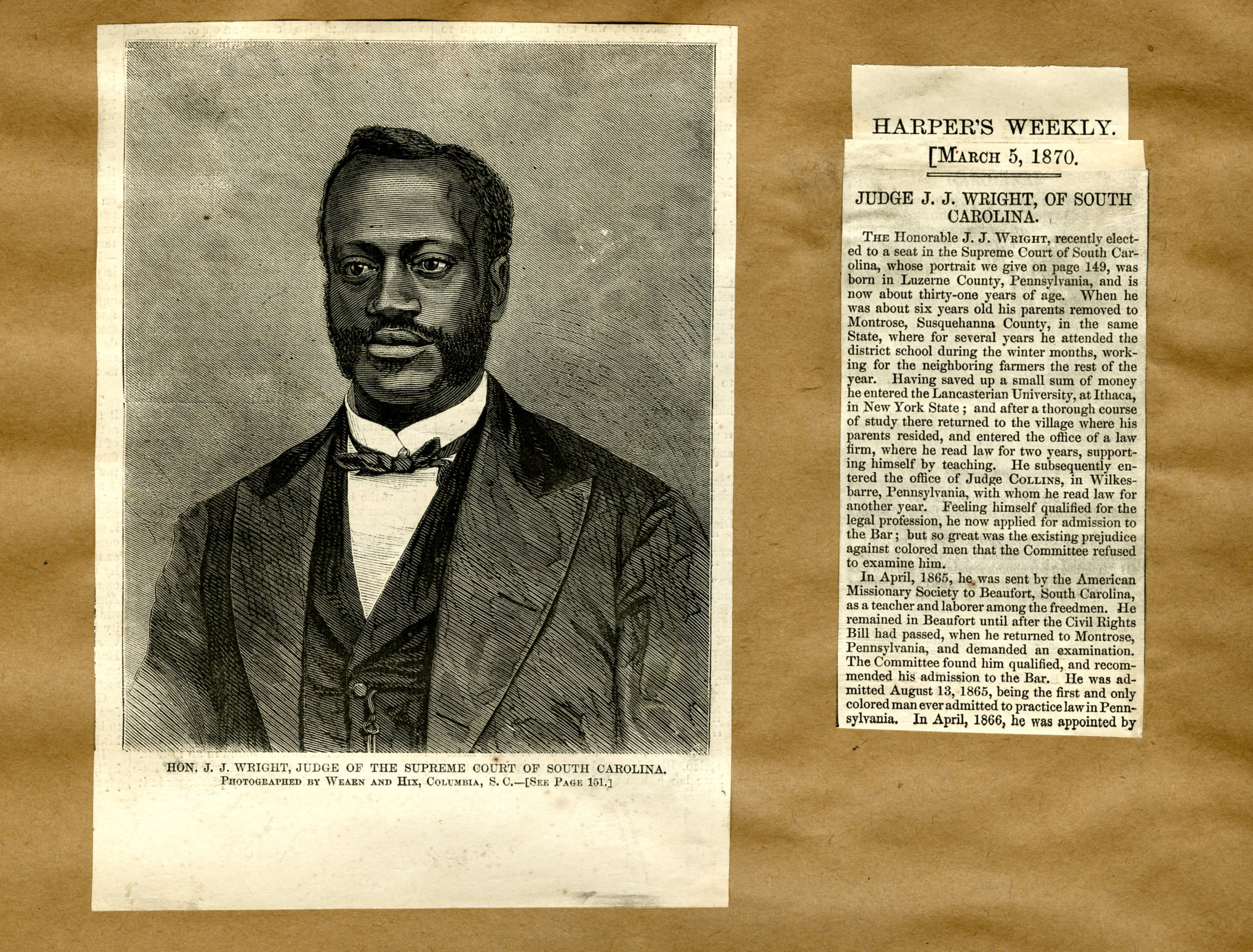

| Click to Examine Judge J.J. Wright, South Carolina Supreme Court, 1870. From “Negro in Politics” Scrapbook, Alexander Gumby Collection of Negroiana, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. |

Questions:

- Read the testimony recorded by Charles Stearns. Who are the different people and groups represented in this testimony? What obstacles to voting are reported by these witnesses?

- Examine the articles and images depicting John W. Menard and Judge J.J. Wright. What biographical information stands out to you? How do these men present themselves in their portraits?

- Consider the open, public, violence depicted and discussed in these sources. This factor was often ignored in Jim Crow histories of the period. How does the presence of physical force in the electoral process change the story of black politics in Reconstruction?

Section 6 Primary Sources

|

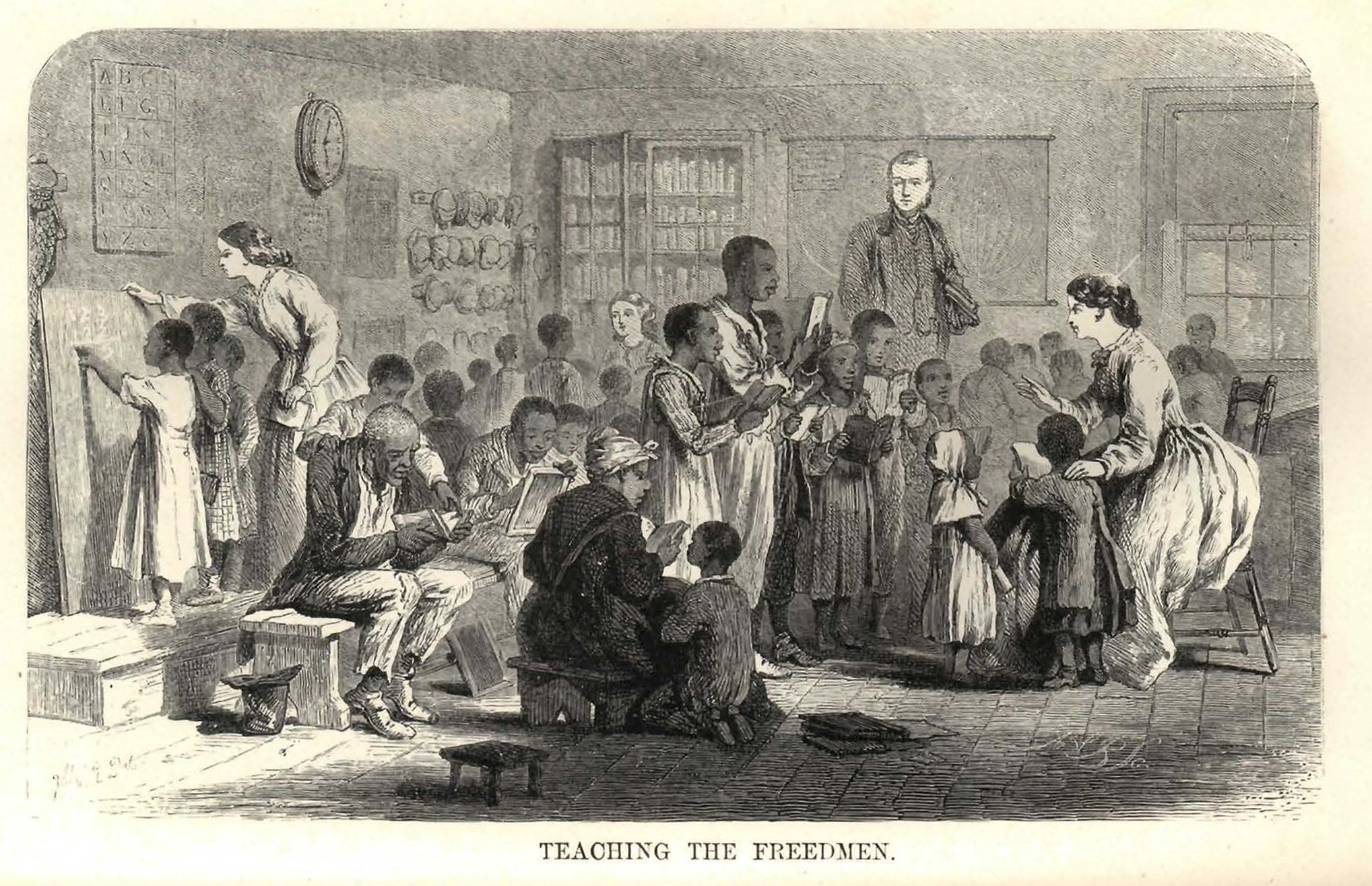

| Click to Examine “Teaching the Freedmen.” From J.T. Trowbridge, The South: A Tour of Its Battlefields and Ruined Cities, a Journey through the Desolated States, and Talks with the People, Hartford, Conn.: L. Stebbins, 1866. |

One of the major achievements of Southern Republican governments during Reconstruction was the establishment of public schools serving both black and white children. From the earliest days of Reconstruction, freedpeople demonstrated an impressive thirst for literacy and education, resources that were denied to them under slavery. Children and adults alike seized the opportunity to learn to read and write.

Freedmen’s aid societies and the Freedmen’s Bureau set up schools staffed by Northern white teachers, but the former slaves soon established additional schools of their own. As Republicans attained public offices, state governments built upon these early efforts by creating a public school system and aiding in the founding of new colleges serving black students. The vast majority of these schools and colleges were segregated by race, but these institutions represented a major step forward for education in the South.

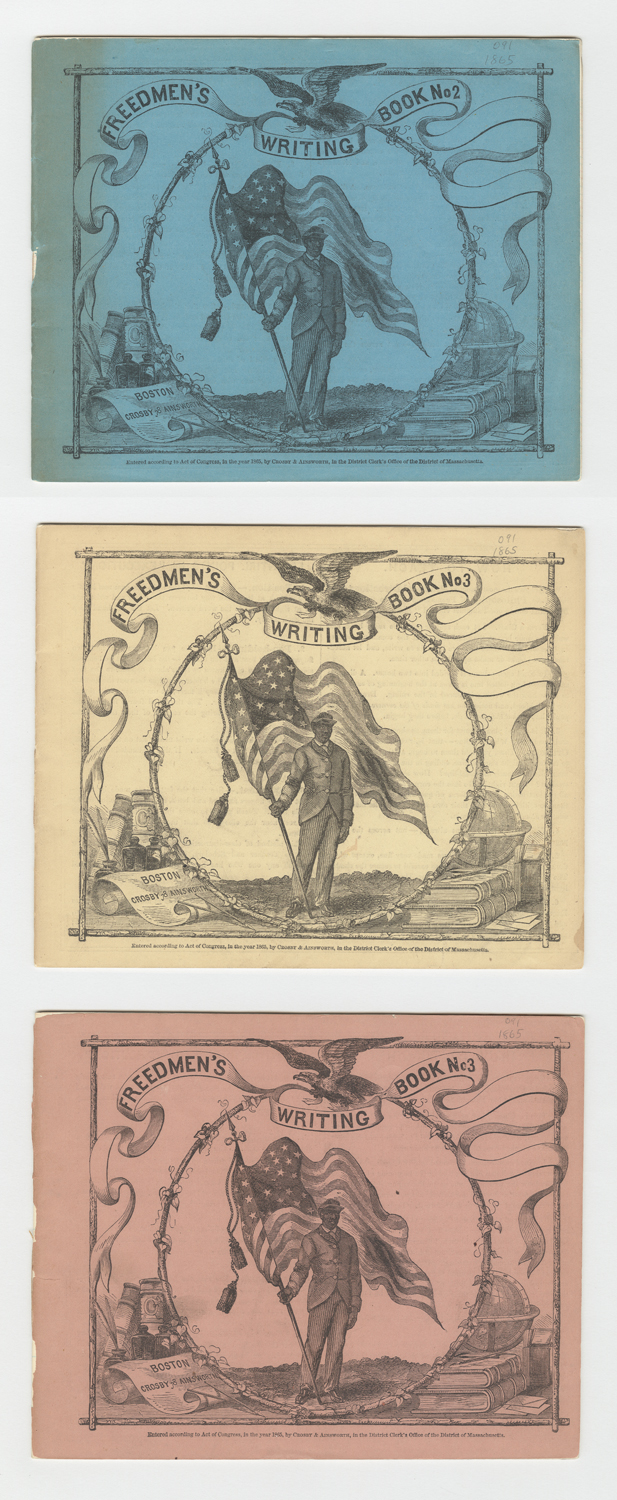

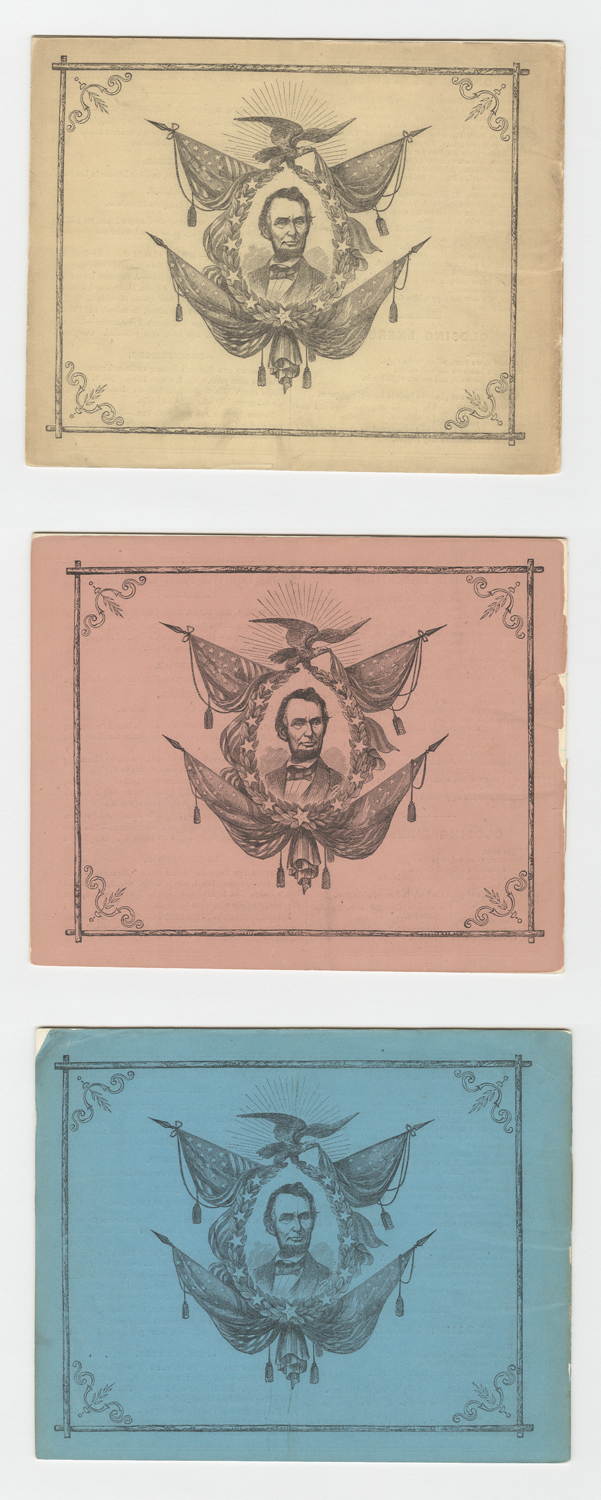

This week’s primary sources relate to the education of former slaves during Reconstruction. The image above shows a crowded classroom staffed by Northern white teachers. The images below are scanned pages from Freedmen’s Writing Books used during Reconstruction. These workbooks would have been distributed in freedmen’s schools and were used for practicing penmanship. As ephemeral items of daily life, few documents like these survive in archives, making these writing books especially exciting and unique. Examine these primary sources carefully, and then consider the interpretive questions that follow.

Click to Examine |

Click to Examine |

| Freedmen’s Writing Books, Front and Back Covers, Boston: Crosby & Ainsworth, 1865. From the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. | |

|

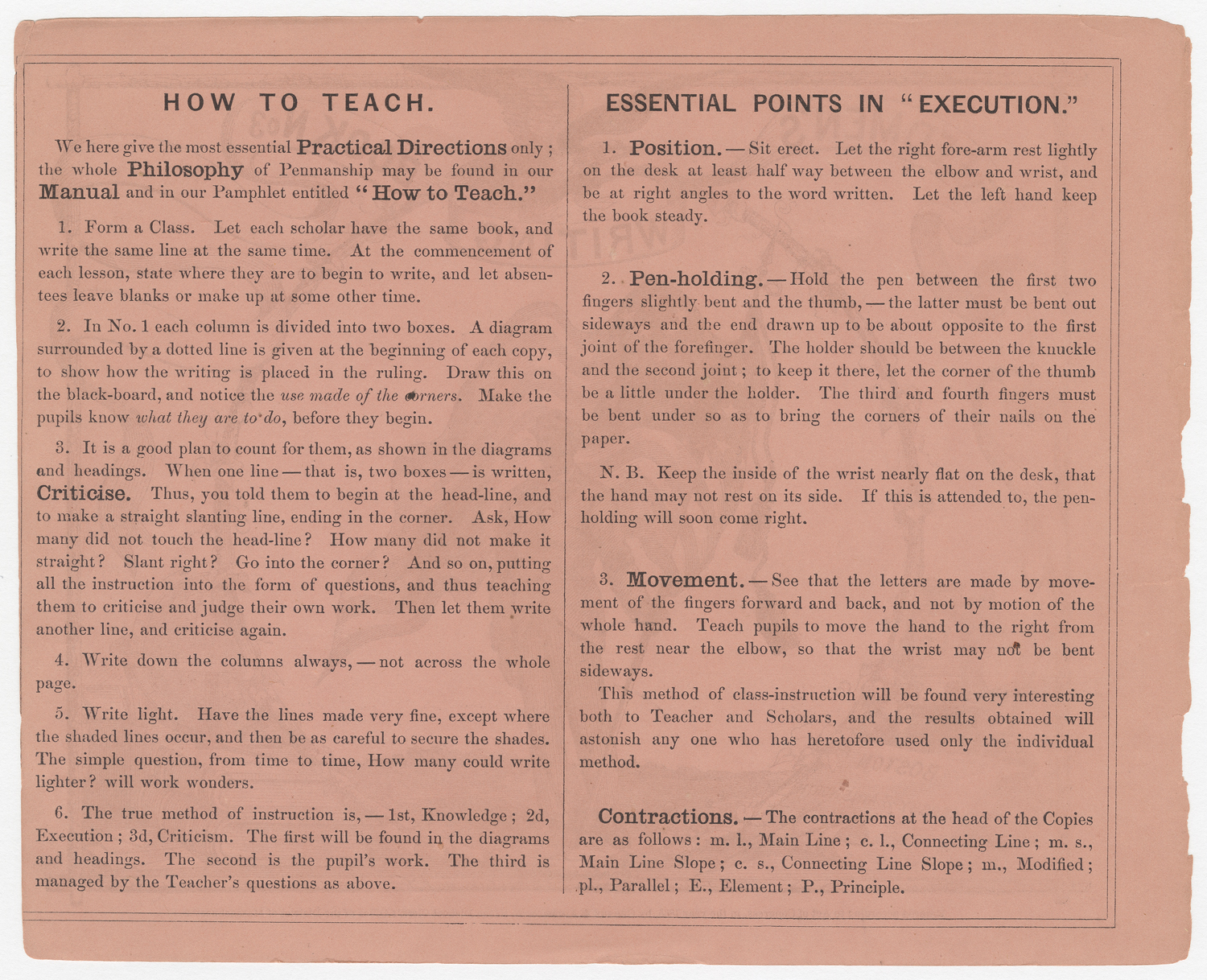

| Click to Examine The inside cover of the Freedmen’s Writing Book offers detailed instructions for posture and pen-holding. |

|

| Click to Examine Each page of the workbook is inscribed with an aphorism for copying. This page includes the word “Amazing” as well as the phrase “A rolling stone gets no moss.” |

Questions

- Consider the visual imagery of the illustration of the freedmen’s school and the covers of the writing books. What details and/or symbols stand out to you? What messages do these images send about the relationship of freedpeople to the North and to the United States?

- Consider the writing book as a pedagogical instrument and read the instructions from the inside cover and the phrase for copying. What lessons is it trying to teach its users?

Section 7 Primary Sources

Founded in 1866 in Tennessee, the Ku Klux Klan rapidly spread throughout the South to launch a “reign of terror against black and white Republicans. The Grant Administration and Congress crushed the Klan with the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871 and by dispatching federal marshals to arrest hundreds of Klan members. Terrorist violence against black Southerners and white Republicans was driven underground for a period of time, although the end of federal Reconstruction in 1877 saw the beginnings of a resurgence of white supremacy in the South, culminating with the elaboration of Jim Crow laws in the 1880s and 90s and the rise of lynchings, both of which persisted through the 1960s.

|

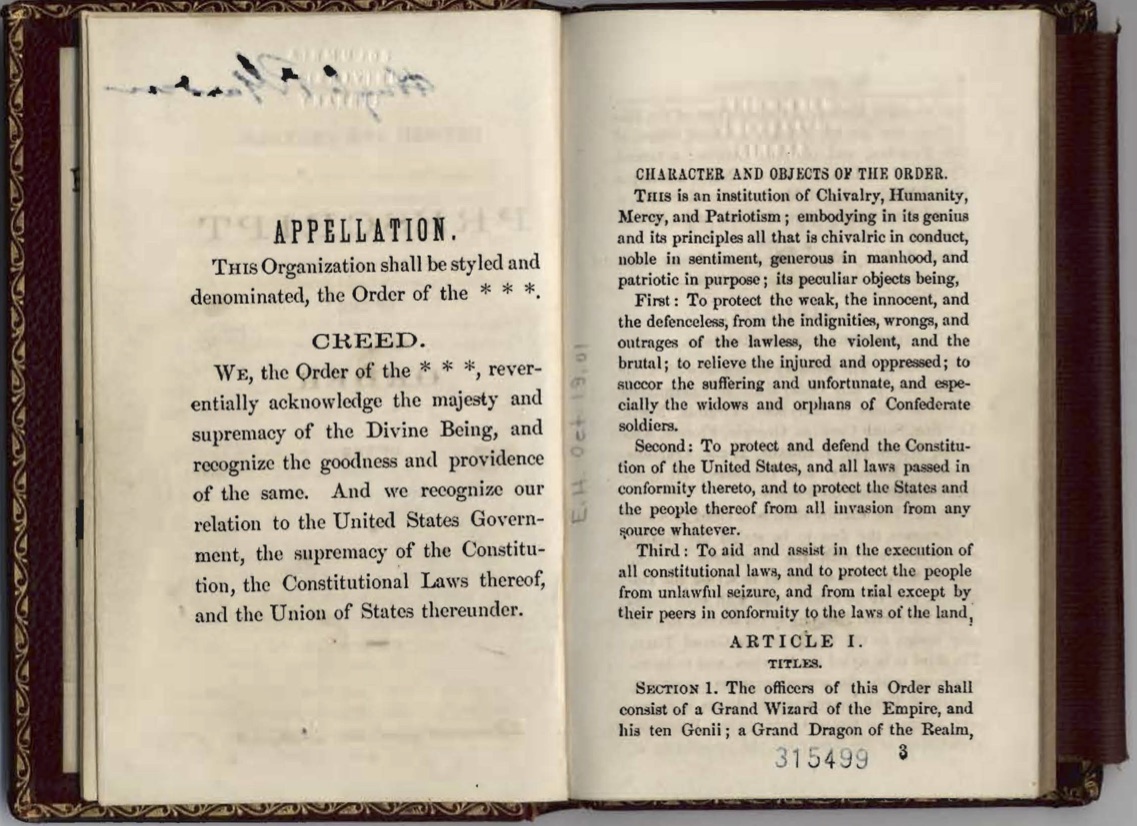

| Click to Examine Appellation and Creed, Ku Klux Klan, Revised and Amended Prescript of the Order of the ***, [Pulaski, Tenn., 1868]. From the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. |

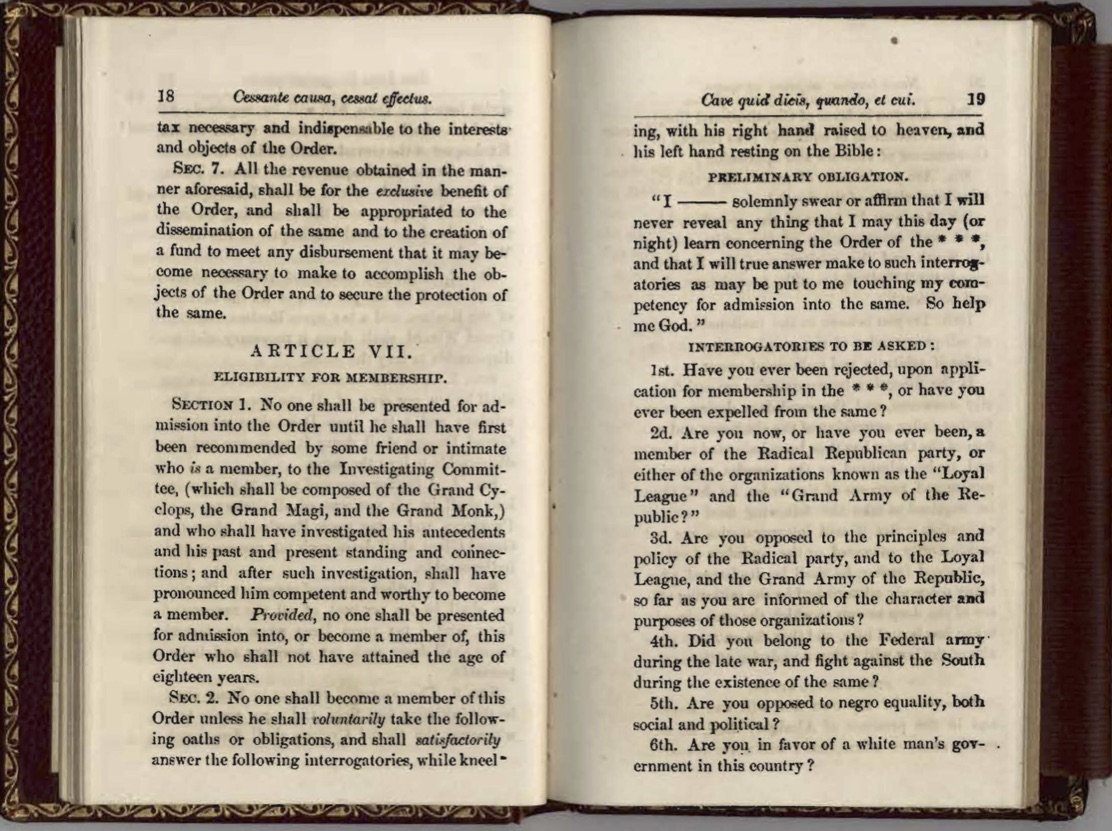

This week’s primary source documents the reign of the Klan during Reconstruction, and it also points to the persistence of virulent racism after this time period. This pamphlet is a copy of the Klan’s Prescripts, specifying the various officers and rules of the organization.

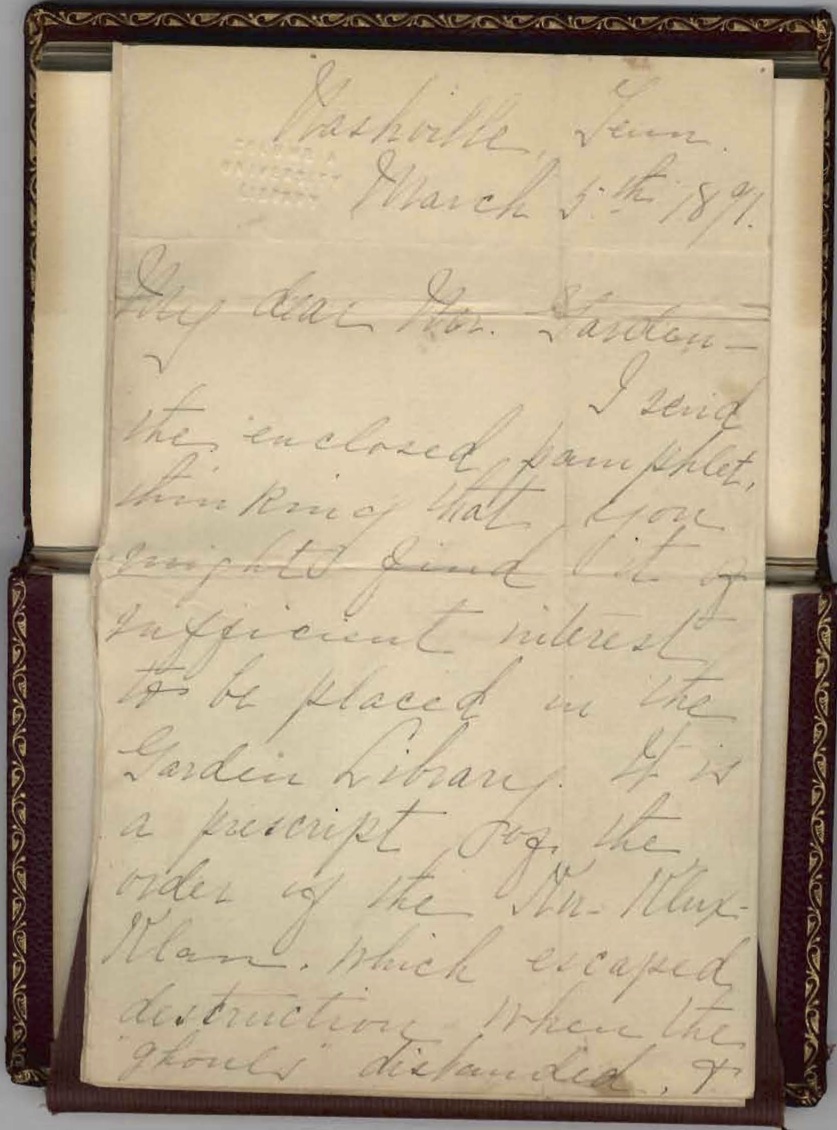

One interesting aspect of this source is the story of how it wound up in Columbia University’s Library. In 1891, a woman named Nellie Porterfield, living in Nashville, Tennessee, donated this pamphlet to the Garden Library of the New York Southern Society. The Southern Society was an organization of white Southern men living in New York City active from 1886 through the 1920s. This organization originally maintained its own library, the Garden Library, but it eventually donated its collections to the Columbia University Library.

The Southern Society published a yearbook documenting its membership as well as yearly speeches by its officers as well as various Southern politicians. These yearbooks offer a glimpse into the Society’s mindset and mission. The speeches frequently offer a reconciliationist view of the Civil War and a triumphal narrative of the South in the Jim Crow era. The inclusion of a Ku Klux Klan pamphlet in the collections of the Society’s library is a telling reminder of enduring racism that permeated the North and the South after Reconstruction.

|

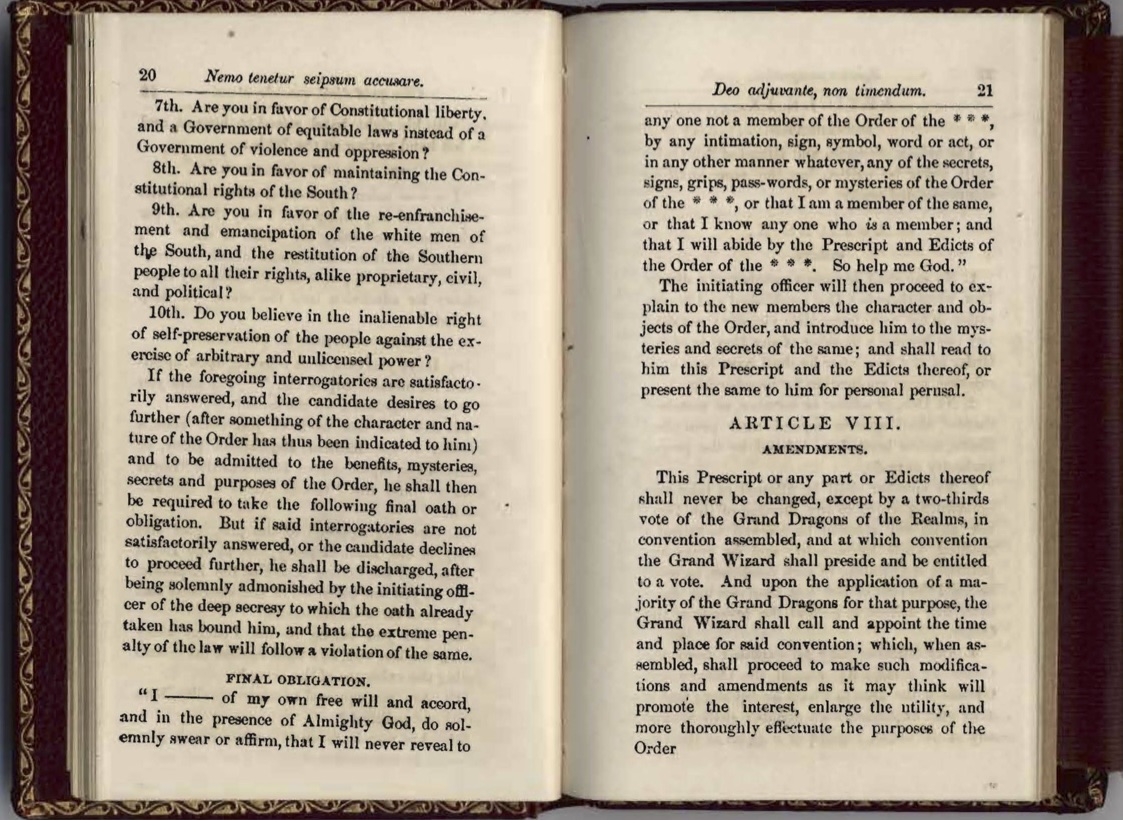

| Click to Examine Eligibility for Membership. These pages detail the questions prospective members would have to answer “satisfactorily” in order to join the Klan. |

|

| Click to Examine Eligibility for Membership continued. |

|

| Click to Examine This letter, dated 1891, is bound with the Prescript pamphlet. See transcript below. |

|

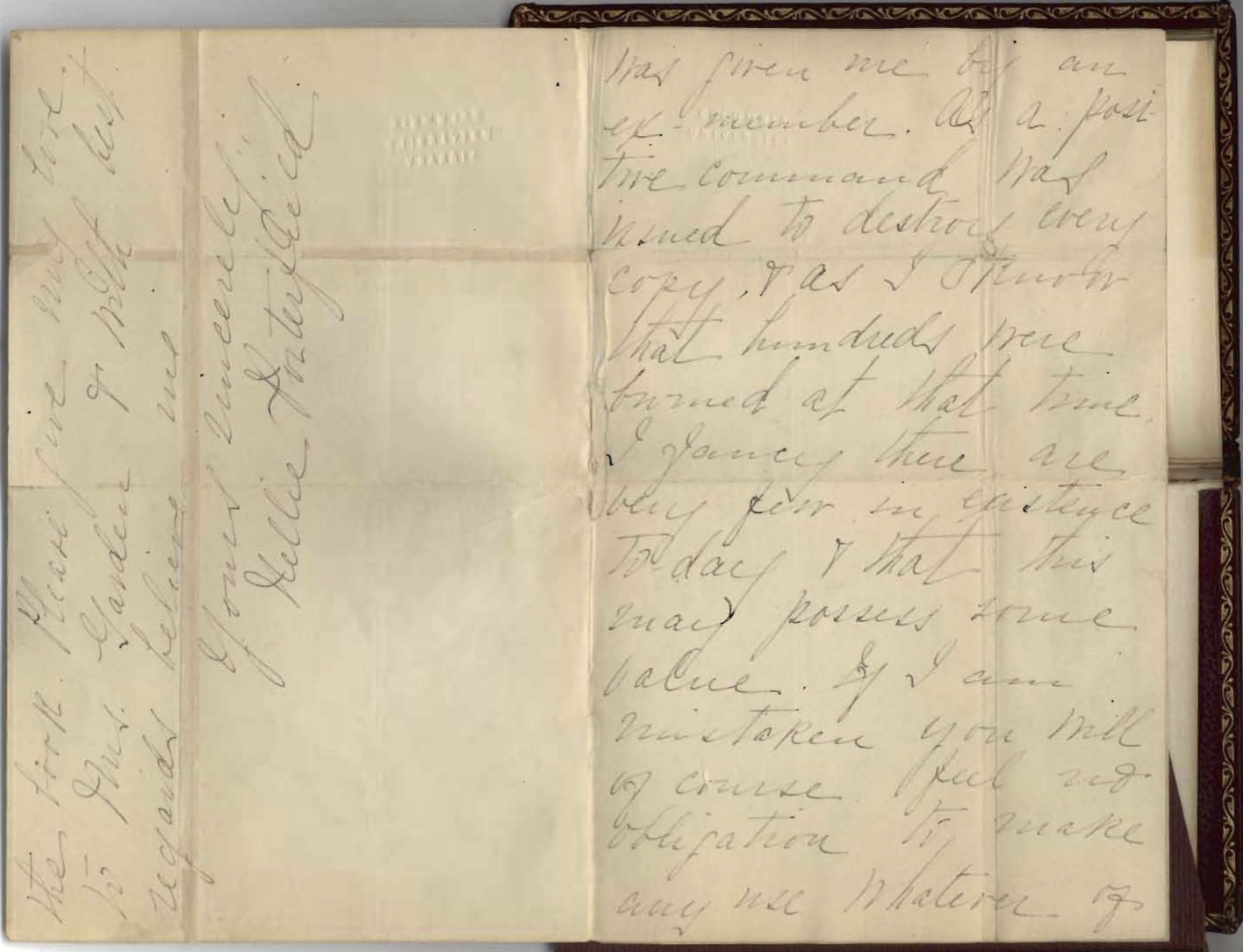

| Click to Examine The letter is signed by Nellie Porterfield, who explains that she is sending the pamphlet as a donation to the Garden Library of the New York Southern Society. |

Transcript:

Nashville, Tenn.

March 5th 1891

My dear Mr. Garden—

I send the enclosed pamphlet, thinking that you might find it of sufficient interest to be placed in the Garden Library. It is a prescript of the order of the Ku-Klux-Klan, which escaped destruction when the “ghouls” disbanded, & was given me by an ex-member. As a positive command was issued to destroy every copy, & as I know that hundreds were burned at that time, I fancy there are very few in existence to-day & that this may possess some value. If I am mistaken you will of course feel no obligation to make any use whatever of the book. Please give my love to Mrs. Garden & with best regards believe me

Yours sincerely,

Nellie Porterfield

Questions

After examining the images and transcript, consider these questions:

- For most readers today, this pamphlet stands out as a horrifying example of racism and terrorism in the history of the United States. From this point of view, it may be difficult at first to find historical value in this document. Thinking as a historian, what can you learn from this source? Why is it important to examine sources that illuminate the ugly parts of history as well as the inspiring ones?

- Examine the section titled “Interrogatories to be Asked.” What stands out to you about these questions, which would determine a candidate’s eligibility for membership in the KKK? Which question or questions seem most important to the mission of the Klan?

- Examine the text of the letter included in the pamphlet. What does knowing the story of how this pamphlet ended up in Columbia’s Rare Books Library add to your understanding of this source?

SECTION 8 PRIMARY SOURCES

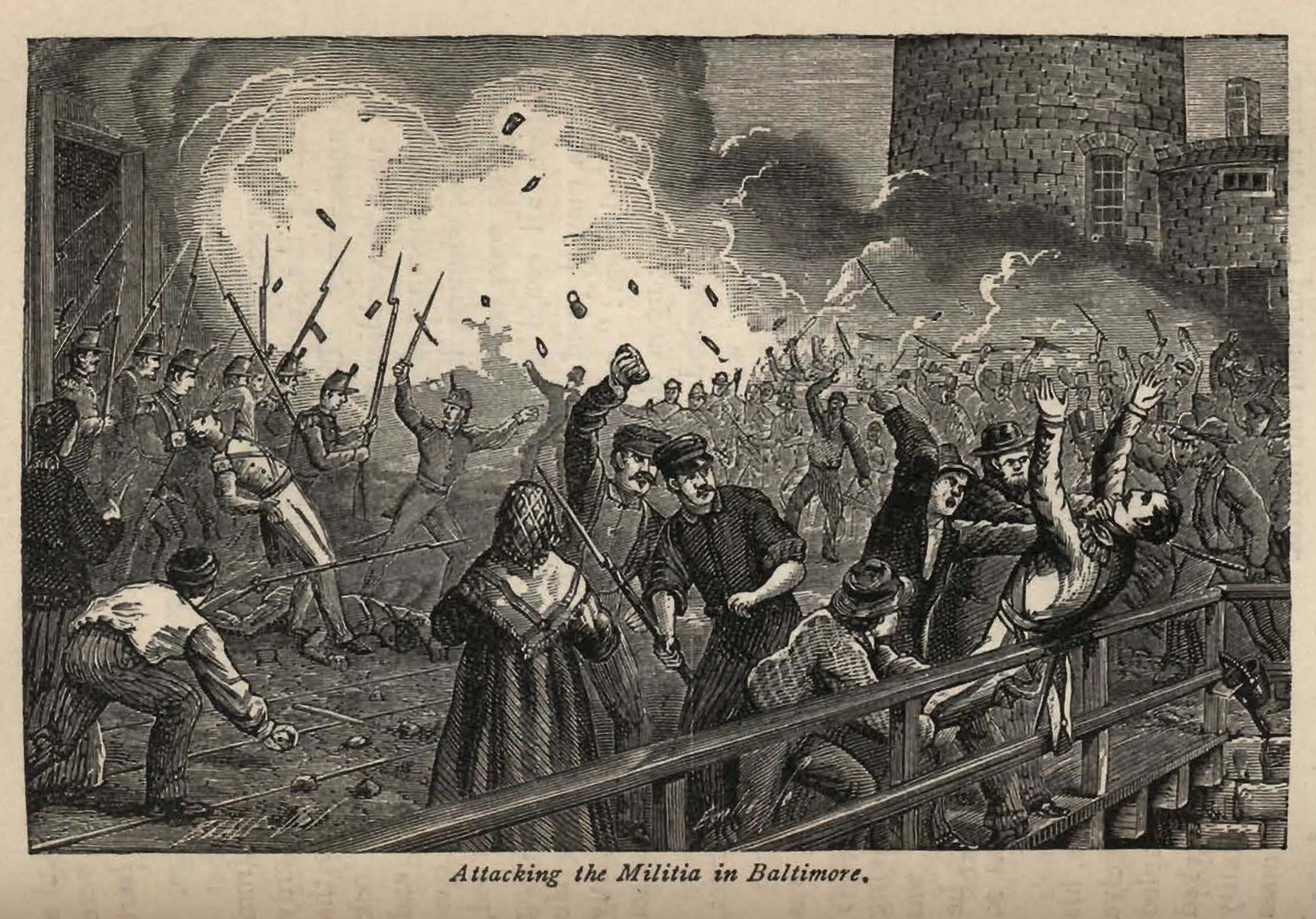

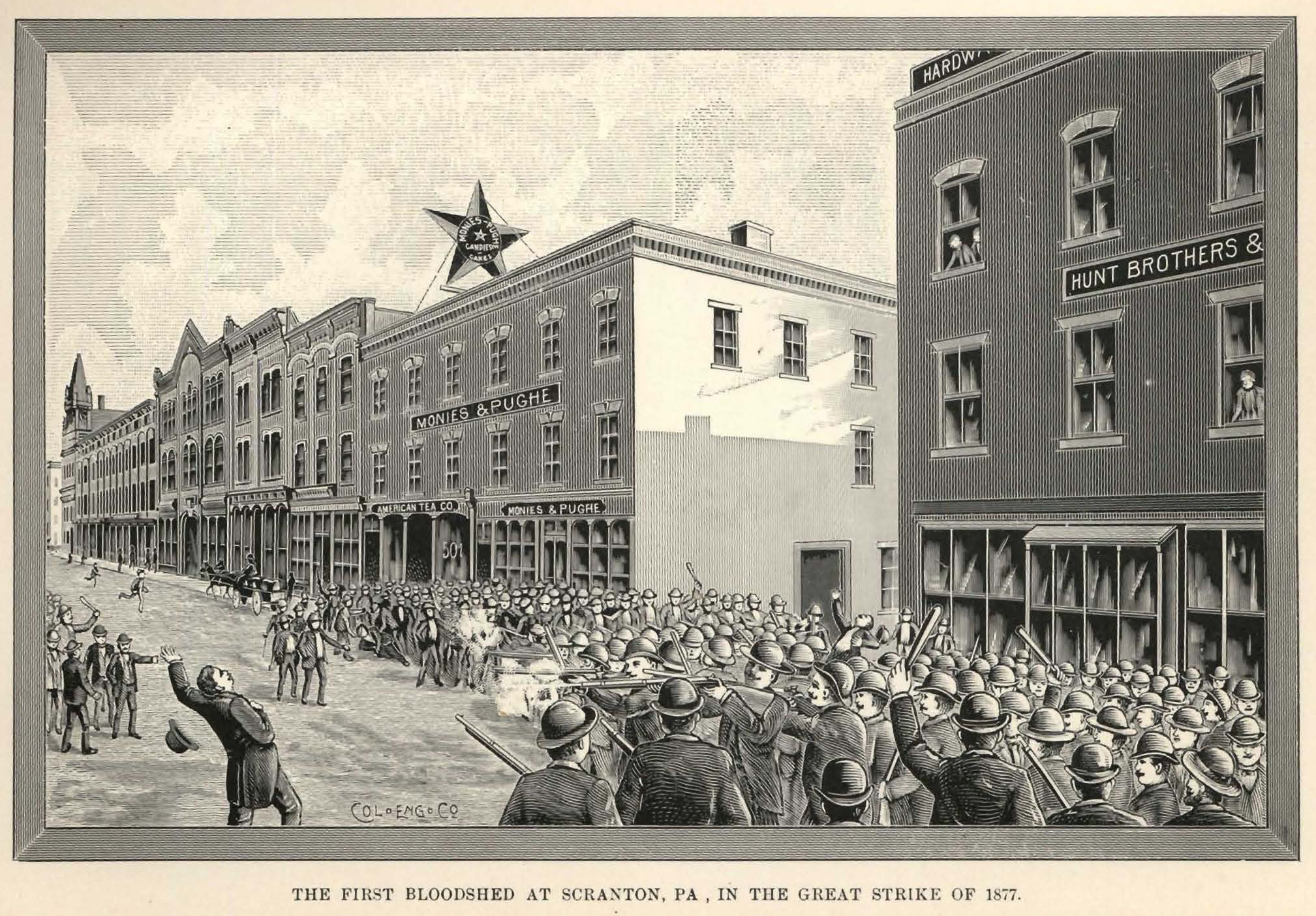

Already suffering from an industrial depression during the summer of 1877, workers for the Baltimore and Ohio railroad erupted in protests at the news that the company was planning yet another reduction of salaries. Beginning in Martinsburg, West Virginia – only 20 miles from Harper’s Ferry, where John Brown’s raid in 1859 had catalyzed the Civil War – the spontaneous strike spread along the railroad lines to the north and west. President Hayes called out federal troops to protect the nation from this new “insurrection,” but the use of the military against laborers merely intensified the people’s anger. In Baltimore, militiamen fired on the crowds, killing eleven and leaving dozens injured. Confrontations erupted in numerous industrial towns and cities, climaxing in Pittsburgh, where another pitched battle left dozens of victims and millions of dollars in property damage. It took more than a month for the soldiery finally to restore law and order. Soon to be recalled as the “Great Strike of 1877,” this epic struggle marked the end of Reconstruction and the commencement of a new era, commonly recalled as the Gilded Age – but also known to historians as the Age of Industrial Violence.

The images and documents below reflect the stark differences of opinion that existed about these issues. Examine them carefully and then answer the interpretive questions that follow.

Click to Examine Click to Examine |

| Illustration from Allan Pinkerton, Strikers, Communists, Tramps and Detectives, New York, G.W. Carleton and Co., 1878. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. This image of the battle in Baltimore comes from a book written by Allan Pinkerton. Already well-known as the founder of a detective agency, which would oppose labor unions in numerous Gilded Age confrontations, Pinkerton decried the Strikers of 1877 as “malcontents” and dismissed their efforts as “communistic madness” and a “most imbecile fiasco." |

Click to Examine Click to Examine

Illustration from Terence Powderly, Thirty Years of Labor, Columbus, Excelsior Publishing House, 1889. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University A second view of industrial conflict in 1877 comes from a book by Terence Powderly, who would become the leader of the Knights of Labor – the most powerful labor organization of the early Gilded Age. This image depicts a scene in Scranton, PA., when armed citizens fired on unarmed strikers, killing three. Powderly’s Knights of Labor did not directly participate in the Strike of 1877, but the union leader praised the railroad unions, avowing that “had it been left to them there would never have been an act of violence committed during the strike.” |

Interpretive Questions:

- Examine the two book illustrations. How are the authors’ politics graphically represented? Be specific. Look at portrayals of the combatants (laborers, soldiers, militiamen, citizens), note the way figures are grouped or isolated, discuss the presence or absence of violence, chaos, action, emotion, etc. What messages do these image choices convey?

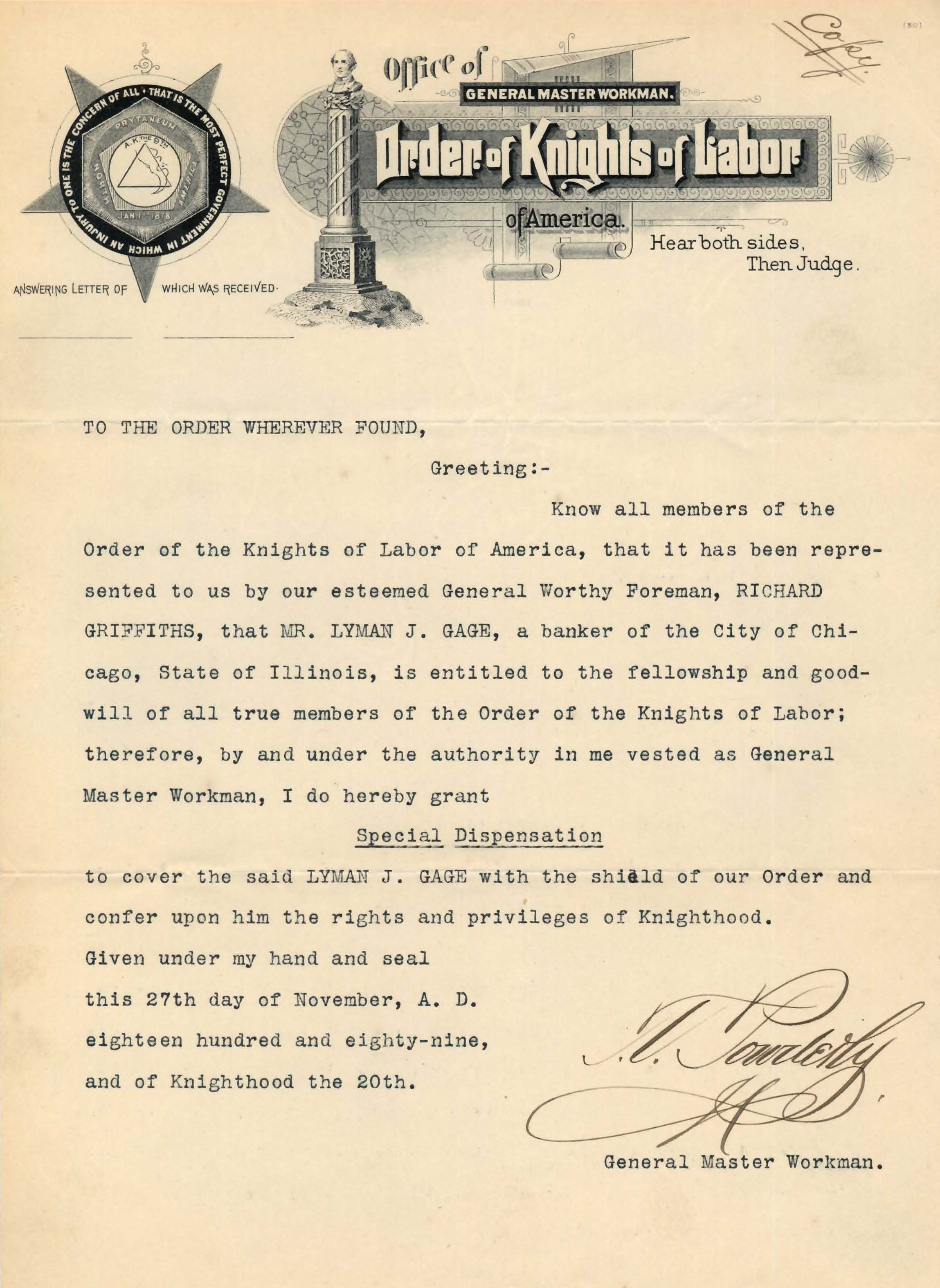

- The letter from Terence Powderly features mottos and symbolic representations significant to the Knights of Labor. What can you infer about the organization from the choices of decoration that adorn this letter? What symbolism is present and what is absent? How is the group trying to represent itself to the person who received this communication?

- The recipient of the letter is a banker from Chicago. It was highly unusual for the union to grant “fellowship and good will” to a prominent businessman. Usually, the following people were forbidden from joining: Asians, bankers, doctors, lawyers, stockholders, and liquor manufacturers. What can we infer from this list about the way the Knights viewed the social conflicts of their era?