Section 10 Primary Sources

Lincoln’s Election and the Secession Crisis, 1860-1861

Abraham Lincoln is remembered as a renowned orator, and he was as conscious of the power of images as of words. There were thousands of images of Lincoln produced during and after his lifetime, including photographs, prints, sculptures, and cartoons. The objects pictured below are unique in that they are both three-dimensional casts reflecting Lincoln’s “true” physical appearance. Life masks like the one pictured below were an effective way to disseminate accurate likenesses of public figures before the widespread use of photography. The sculptor Leonard Volk took the original plaster casts for both of these objects around the time that Lincoln received the Republican nomination for the 1860 presidential election.

|

| Click to Analyze Abraham Lincoln Life Mask, 1860. Abraham Lincoln Portraits and Memorabilia, RBML, Columbia University. |

|

|

| Click to Analyze | Click to Analyze |

| Bronze Cast of Lincoln’s Hands, 1860. Abraham Lincoln Portraits and Memorabilia, RBML, Columbia University. | |

Questions

- Considering how uncomfortable it was for the model to sit for these castings, why do you think Lincoln would have agreed to participate in the process?

- These masks leave a stark, surprising, and almost macabre impression on the modern viewer. They were, however, a fairly common method in the nineteenth century for spreading information about the physical appearance of public figures. In your opinion, how would an audience of Lincoln’s contemporaries experience the sight of these casts? Would their emotional response have been different than ours today?

- Alongside casts like these, the spreading technology of photography enabled Lincoln to become one of the most visible and recognizable presidents to date. How might Lincoln’s visibility have contributed to the perception in the South that his election was a catalyst for secession?

Week 9 Primary Sources

Published eight days after John Brown’s execution, this Philadelphia newspaper features engraved portraits of the protagonists, as well as a detailed depiction of the “scene of the execution.” Examine the images. Do they indicate the partisanship of the newspaper’s publishers, or offer any clues concerning the public feelings about the Harpers Ferry raid

Click to Analyze |

From the Sydney Howard Gay papers, Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library |

You may have noticed a doggerel poem near the center of the page. Examine it more closely in the closeup below, and then answer the analytical questions that follow:

Click to Analyze |

THE FANATIC'S SONG I'll be a Reformer, The Bible doesn’t say so – ‘Tis true I beat my wife, There’ll be murder and blood I know, But stop – I might lose my head, ARIEL. * According to the American Slang Dictionary (1891), “shindy” was defined as “a row, noise or disturbance.” |

Questions

- What is the tone of the poem? How do you interpret the author’s references to the Bible, domestic abuse, and business failures?

- Is this poem wholly critical of John Brown and his actions?

- How do you interpret the last stanza, in particular, compared to the rest of the work?

- How might a historian employ this poem as a piece of evidence in a larger research project concerning northern attitudes toward abolitionism, in general, and John Brown, in particular?

- What further information or sources would be needed in order to craft a more complete interpretation?

Week 8

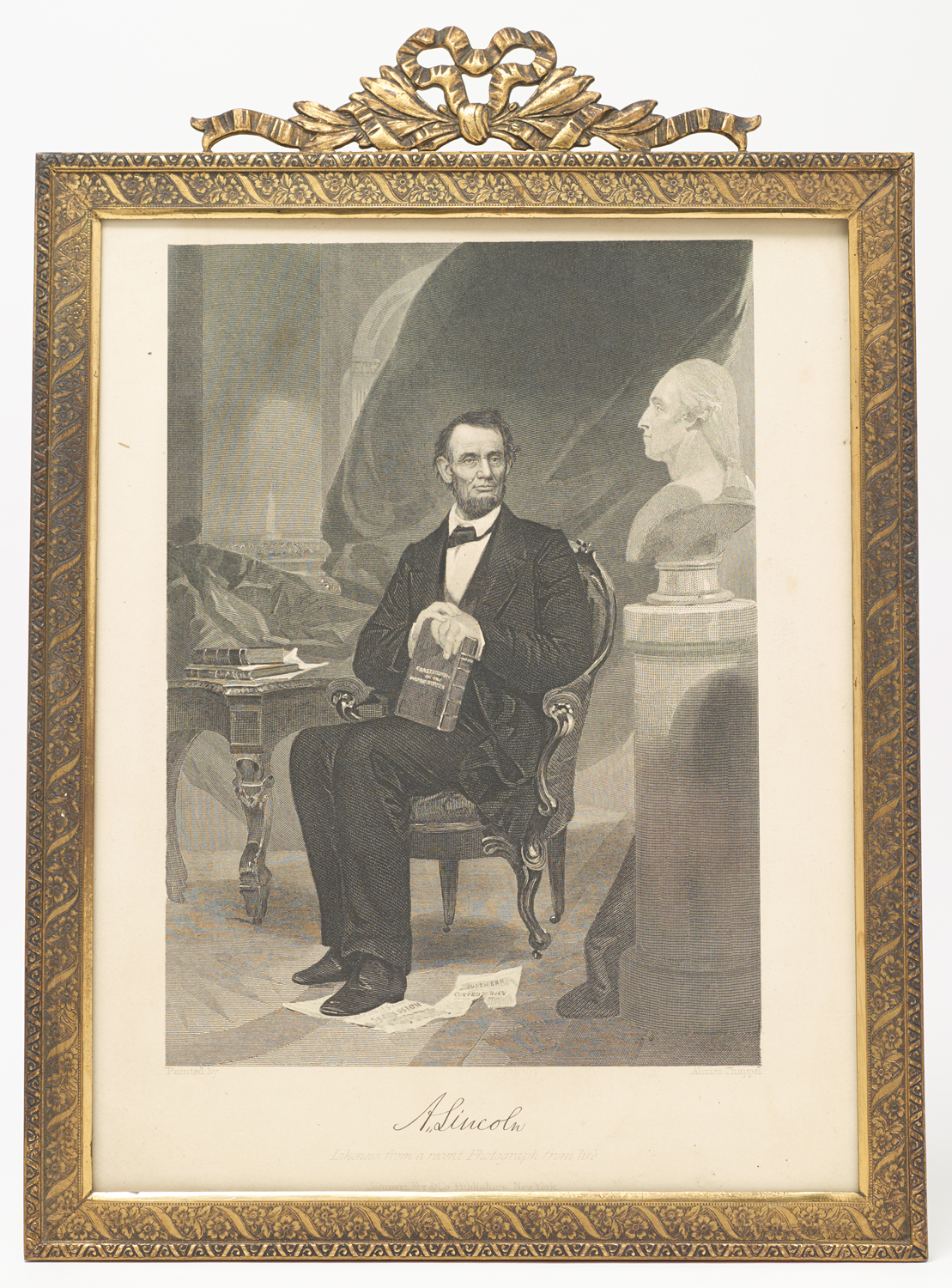

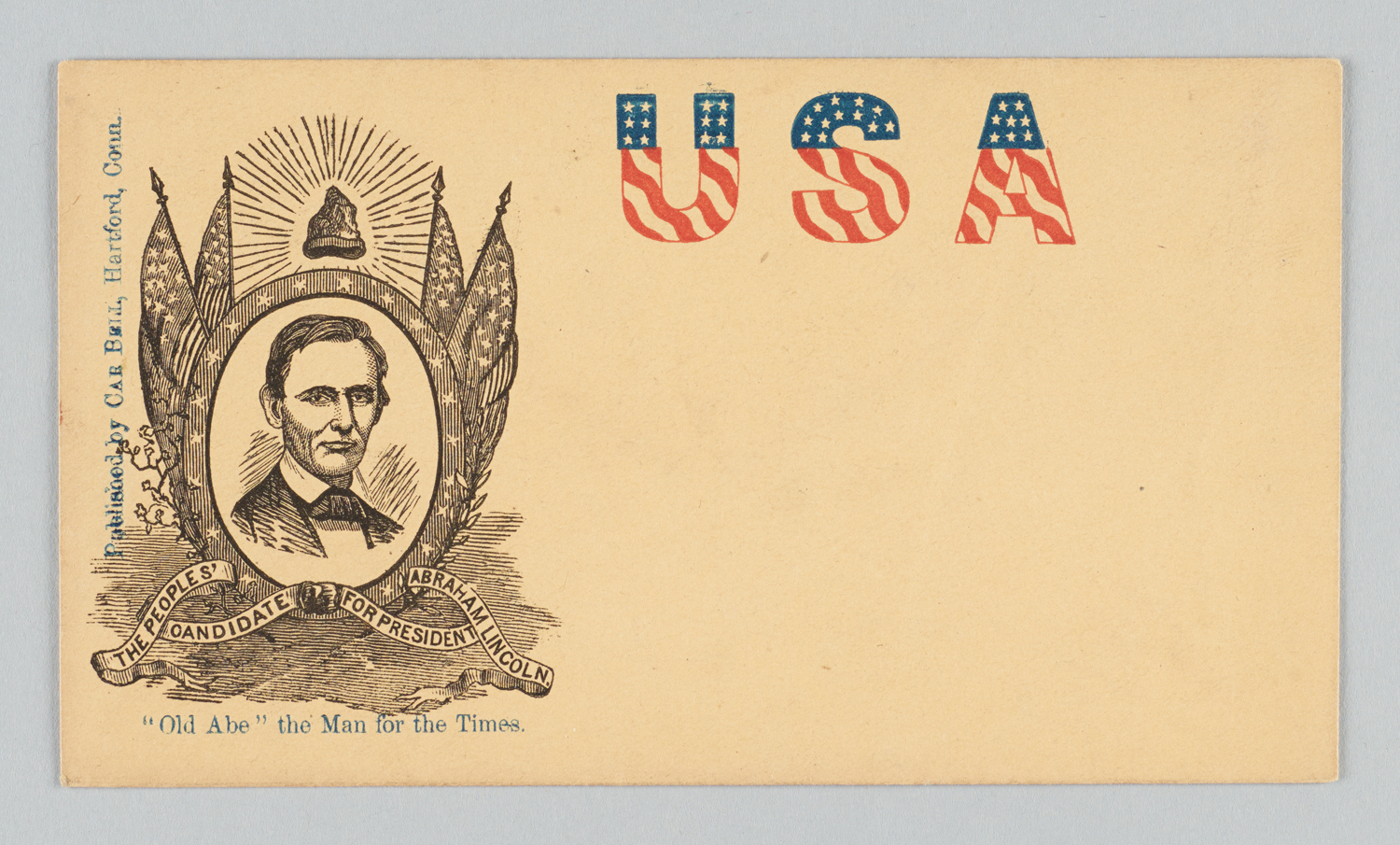

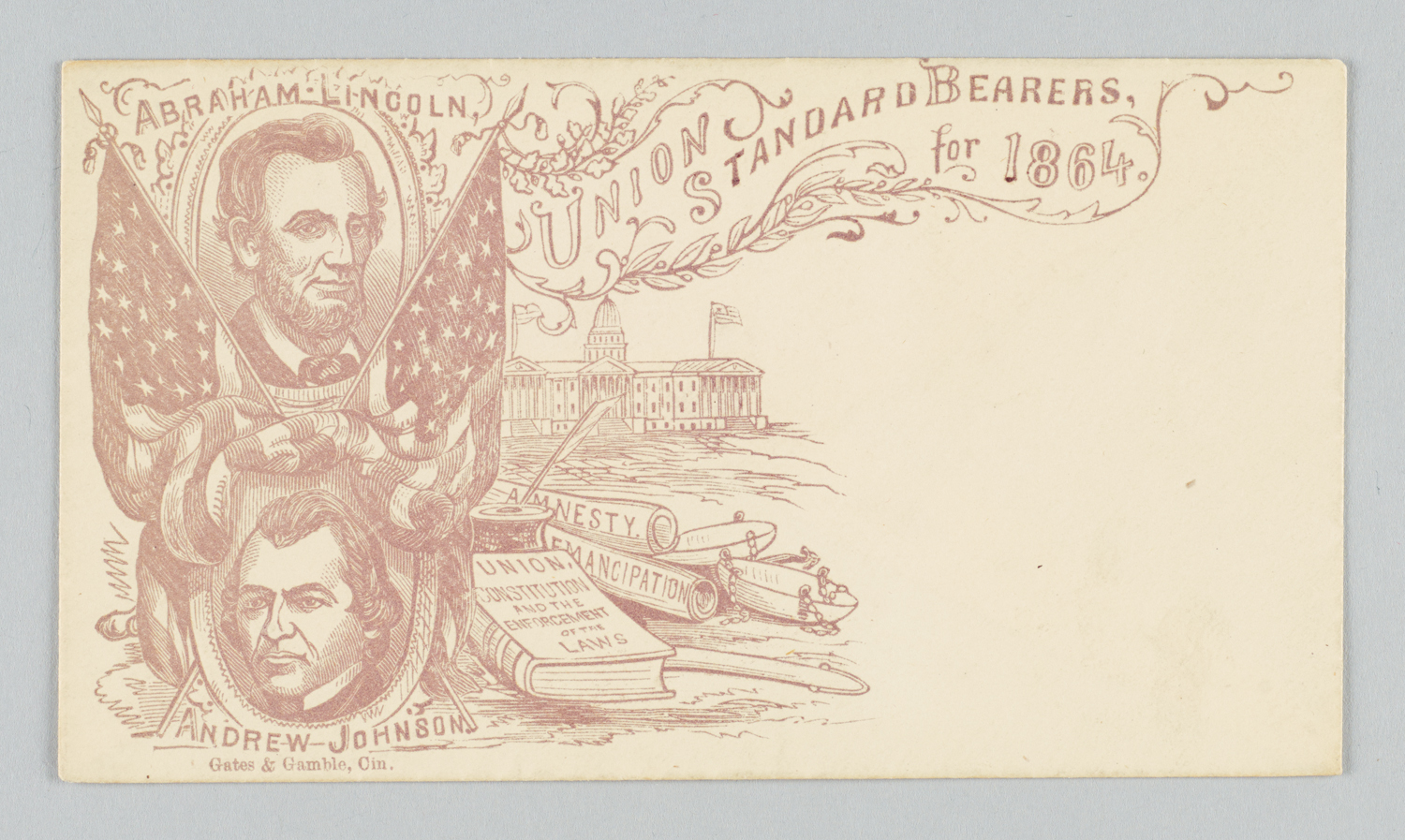

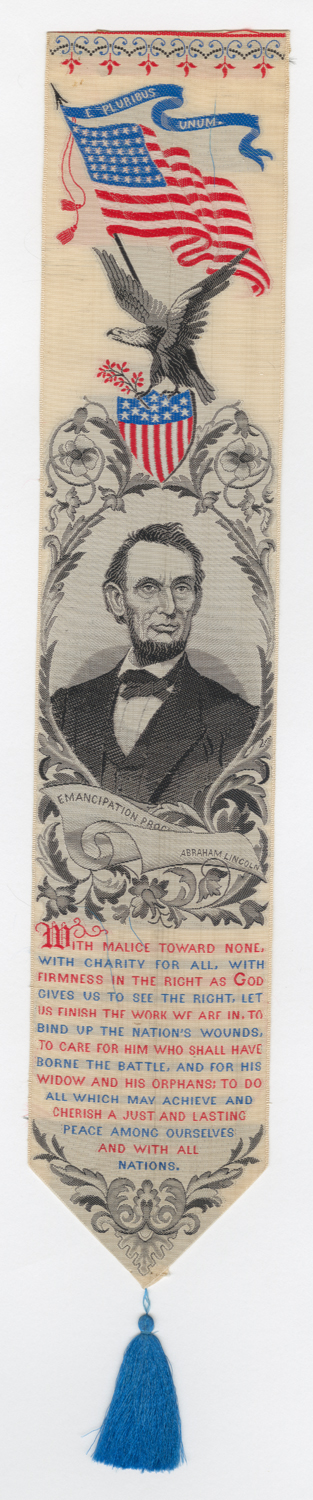

This week’s archival materials relate to the topic of “Lincoln: Myth and Legend.” Below you will find a variety of Lincolniana – i.e., Lincoln-related materials – drawn from the collections of Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library. These objects, intended for mass distribution and consumption, are richly decorated with historical, political, and patriotic symbolism and iconography. Look closely at the images, and then answer the analytical questions below.

Click to Analyze |

Rich in symbolic imagery, this engraving was likely published by Johnson Fry & Co., in New York City, during the early years of the Civil War. The caption reads “A. Lincoln: Likeness from a recent Photograph from life.” From the Abraham Lincoln Portraits and Memorabilia collection, 1860-1940, RBML, Columbia University. |

Click to Analyze |

Circulated as an envelope during the 1860s, this political advertisement touted “Old Abe” as “the Man for the Times.” From the U.S. Civil War Papers, ca. 1850-1917, RBML, Columbia University. From the U.S. Civil War Papers, ca. 1850-1917, RBML, Columbia University. |

Click to Analyze |

This envelope from the 1864 presidential campaign shows Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, the candidates for the Republican (or Union) Party. From the U.S. Civil War Papers, ca. 1850-1917, RBML, Columbia University. |

Click to Analyze |

This silk badge issued during the Columbian World Fair, in Chicago in 1893, depicts Abraham Lincoln and a quotation from the Second Inaugural Address. From the Abraham Lincoln Portraits and Memorabilia collection, 1860-1940, RBML, Columbia University. |

These objects display rich symbolic imagery, including statuary, printed materials, patriotic emblems, and historical references

QUESTIONS:

- What does this iconography say about the priorities and ideas of the creators of these items?

- Can an examination of the images on some of these items suggest different motivations for each one?

Week 6

Primary Sources on Free Labor and the Republicans

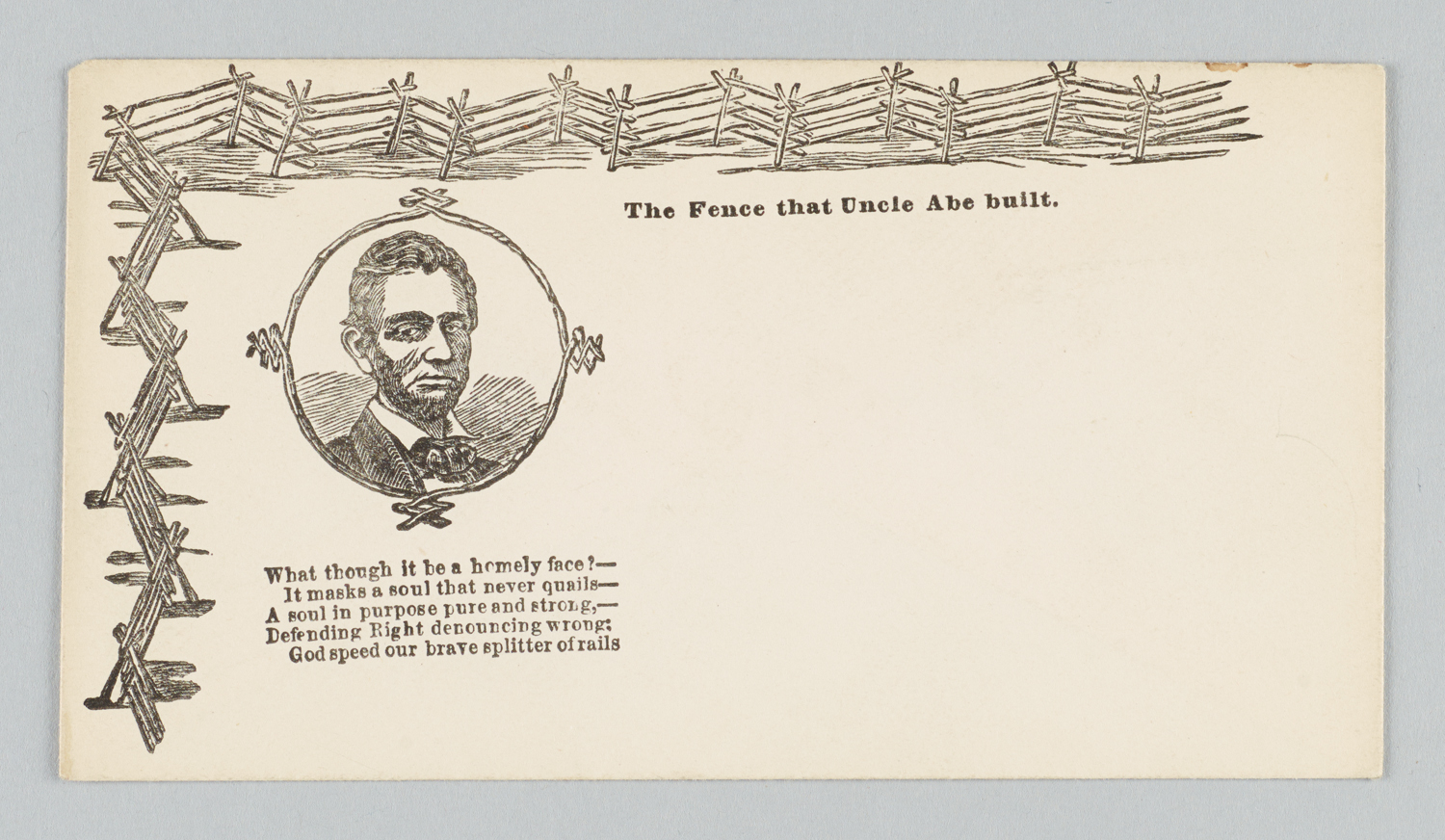

Click to Analyze |

This illustrated envelope dates from the 1860s. Depicting a portrait of Abraham Lincoln and accompanied by a poem, the iconography prominently features “The Fence that Uncle Abe built.” |

Click to Analyze |

This piggy bank in the shape of a rustic frontier home was created in the early 20th century to advertise the Van Dyk tea company. The log cabin claims to represent "the house in which Abraham Lincoln was born." From the Abraham Lincoln Portraits and Memorabilia, 1860-1940. Box 2. Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript Library. |

Questions

Using the suggested queries listed in the “Primary Sources” menu bar tab, examine these two historical objects. Ask yourself these fundamental questions, as you would of any pieces of historical evidence: Why were they created? What was their intended audience? How are they surprising or unexpected?

Now proceed to these analytical questions concerning the imagery of these two objects:

- Abraham Lincoln was a nationally known orator and a successful lawyer. What political or social logic might explain promoting him by focusing on his “homely face” or his reputation as a “brave splitter of rails”? Why was free labor an effective platform for the early Republican Party?

- Comment on the potential linkages between a piggy bank and Abraham Lincoln’s childhood home. Recall that this object was created decades after Lincoln’s death. What does the durability of these symbols say about free labor ideology and the early years of the Republican Party?

Week 4

As slavery became the storm-center of controversy in the United States, ideologies, politics, discourses, and institutions arose to confront the question from a variety of perspectives. Among the most powerful, destructive, and persistent innovations of this era was the development of a form of racism that bore the imprimatur of objective science. The obsessive elaborations characteristic to this variety of thought are evident in the primary document below.

Depicting an “Ethnographic Tableau” of “Specimens of Various Races of Mankind,” this large-scale chart appeared at the front of a volume entitled Indigenous Races of The Earth, which was published in Philadelphia in 1857.

Examine this document using the questions described in the “Primary Sources” menu tab. Then consider some of the questions below:

- How might this document have been used as a racist justification for the institution of slavery?

- What does this method of classification reveal about the assumptions or beliefs of its creators?

- So far, many of the primary-source documents in this course have focused on slavery as an economic institution. How does this document help to illuminate social and cultural aspects of the United States as a slave society prior to the Civil War?

- How does this source challenge or confirm your expectations of the relationship of scientific objectivity to politics and ideology?

Week 3

|

|

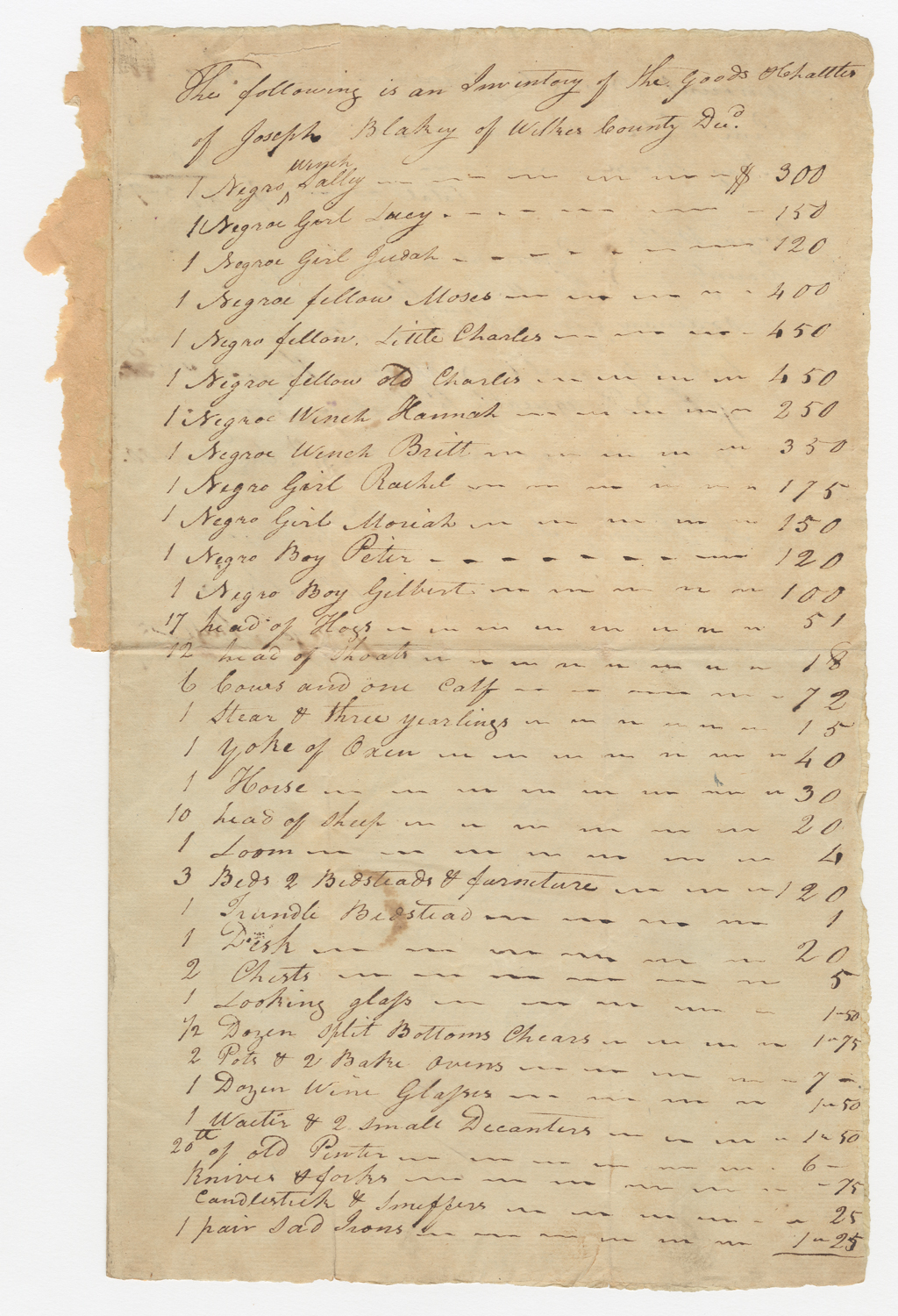

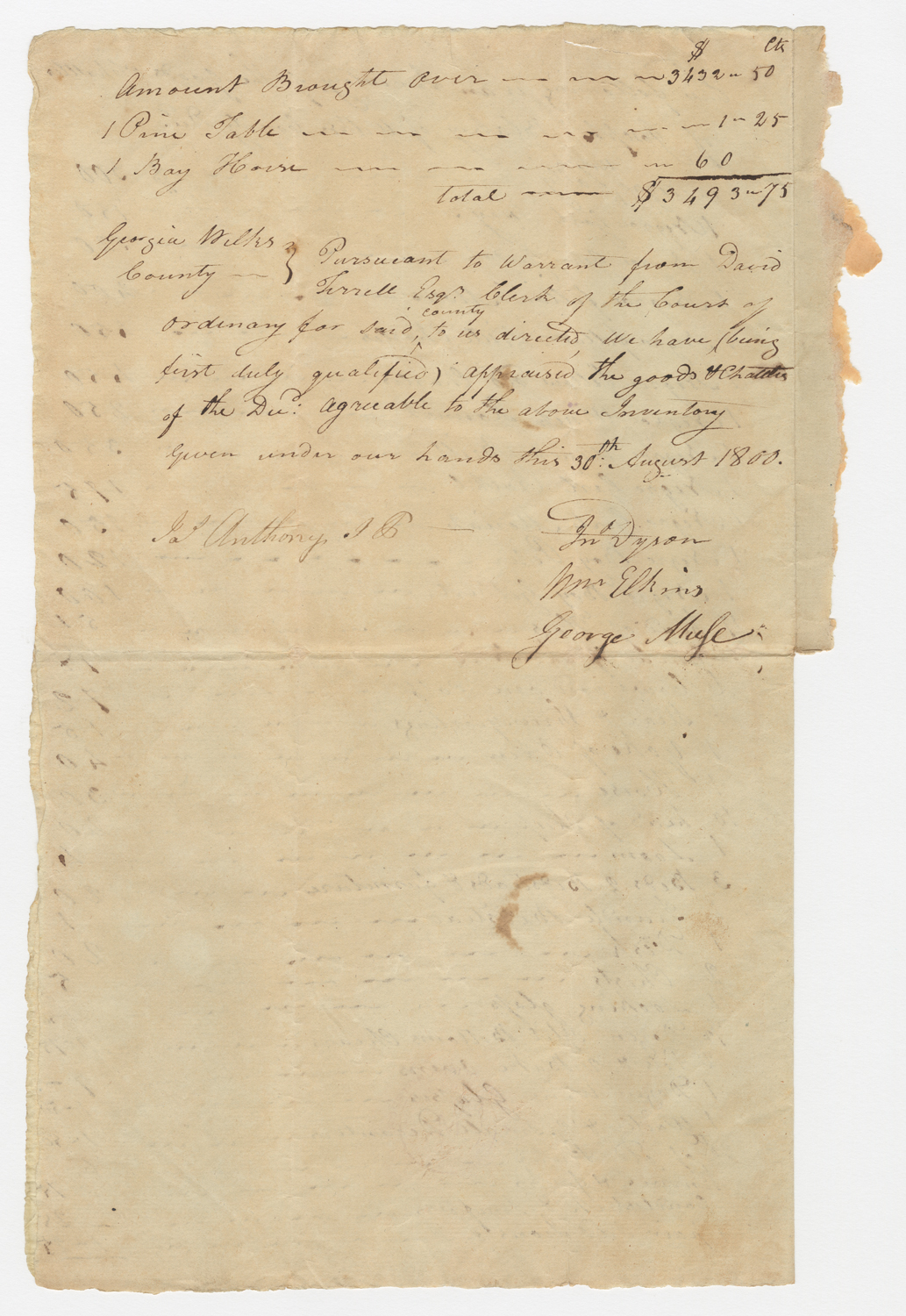

| Click on documents to examine Inventory of the Goods of Chattel, Joseph Blakey of Wilkes County, Georgia, 1800. From the Slavery Collection, Columbia University, RBML |

|

This document is an inventory and valuation of property belonging to one Joseph Blakey, a Georgia plantation owner, who died on January 7, 1800. A few months later, in August 1800, a man named Bolling Anthony was appointed as guardian of Blakey’s three orphaned children. This inventory of goods was then created to catalog the possessions of the deceased.

Examine this document using the fundamental questions discussed in previous weeks. In particular, consider these points: What was the document’s possible purpose? What can it tell us about slavery at the start of the nineteenth century? What further questions does it raise for you? Once you have asked these fundamental questions, look at the historical interpretations listed below.

HISTORICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF A PRIMARY SOURCE

This week’s course materials are about historical interpretations of slavery and the Civil War. Over time ideas and arguments have changed. But at any given moment historians from different fields will ask very different types of questions. In this exercise, three historians from different fields have looked at this one primary-source document to consider how they might use it as evidence. Notice how one document can open up multiple avenues of historical inquiry. Do their questions and interpretations differ from yours?

Mary Freeman, Historian of Women and Gender

This document identifies each slave by his or her first name, sex, and relative age using terms like “fellow,” “wench,” boy, and girl. It is difficult to tell based on this document what family relationships may have existed among these people. The absence of this information, however, is telling of how the institution of slavery strove to erase these connections. Children born into slavery belonged to their owners, not to their parents. In addition, the term “wench” points to how slaveholders envisioned enslaved women as outside the gender norms assigned to white women. To them, enslaved women were “wenches” who labored in the fields, while their wives were ladies who did not stoop to physical labor. The sexual exploitation of enslaved women by their masters is also related to this perception that they were outsiders to traditional gender roles.

x

Mookie Kideckel, Environmental Historian

For an environmental historian, this document provides many clues as to how human interaction with the natural world enabled the system of slavery to function. In isolation, it cannot tell us as much as we might like, but it still raises potent questions. The lives of slaves could vary a great deal depending on what type of crop they planted, how other natural conditions manifested themselves on the plantation, or what "nature"--in the form of backwoods and personal gardens--slaves had access to. In this document, we might ask how the many livestock ordered here affected the working day or other facets of slave life. Or, what does the fact that a loom was required tell us about the type of plants they dealt in? Does the relative pricing of slaves to livestock shed any light on the value slaveowners placed on what they considered to be their property. Did weather conditions alter the conditions in which slaves lived? This type of document can give us a glimpse into the way that nature factored into plantation life, providing an even sharper understanding of the lives of everybody involved.

x

Thai Jones, labor Historian

Labor historians are interested in working conditions, the relations between bosses and workers, and the lives of workers in their leisure hours. Few individual documents can provide satisfactory answers to such questions, but the Blakey inventory suggests interesting clues. The list of luxury household goods shows that enslaved labor was providing the Blakeys with sufficient profits to allow the family to invest in such amenities as fine furniture, a looking glass, and fancy dinnerware. It is equally clear that there was not enough of these items for the slaves themselves to have access to them. Thus, one question is: What sorts of material possessions did the slaves have? What were their living quarters like? A labor historian would also want to know more about the work regimes the slaves employed. Given the time and place, it is likely that they operated in a task system, in which individuals were given certain jobs to be completed by a certain time, rather than laboring in gangs under the direct supervision of an overseer. In the task system, once jobs were completed, enslaved people might have the opportunity to hunt, fish, and cultivate gardens. On the one hand this allowed for some autonomy; on the other, it meant owners did not feel obliged to provide their slaves with food or clothing. Since the inventory of household goods clearly does not show enough beds and chairs to accommodate everyone on the farm, it is possible that the enslaved people had ownership of their own personal possessions – of course, it’s also possible that they simply were not provided with such amenities. In general, historians have shown that the material conditions of enslaved people’s lives in this period were especially meager.

x

Questions

In the discussion below, you might consider the following questions:

- What other historical questions do these sources raise for you?

- What other documents or types of sources might you need, in addition to this document, to answer these questions?

Week 2

|

|

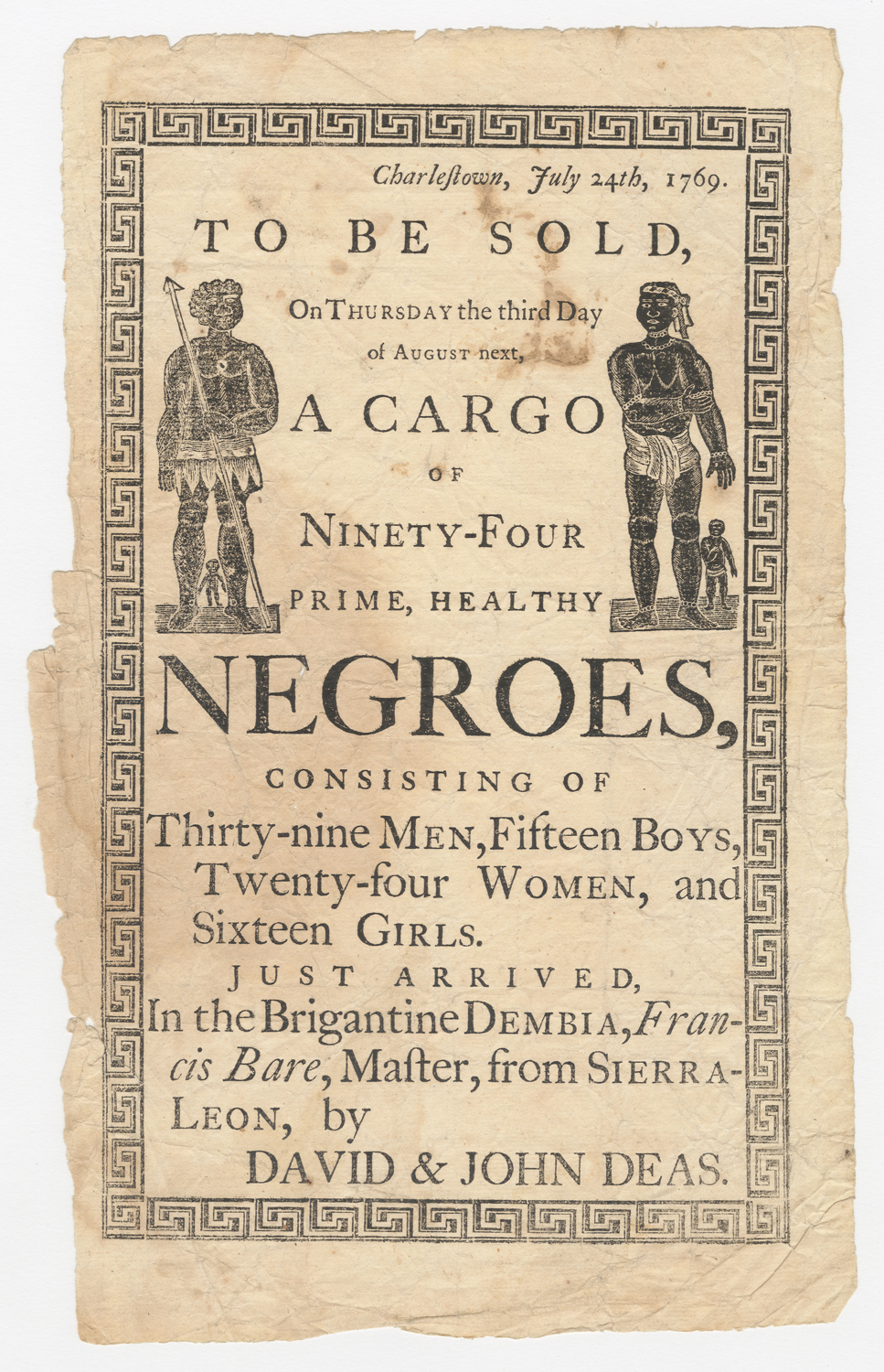

Collection: George A. Plimpton Papers (Box 52) Columbia University, RBML. |

A primary source is a document, image, or artifact that provides firsthand or eyewitness information about a particular historical person, event, or idea. Typical examples of primary sources include letters, diaries, newspapers, photographs, paintings, maps, and oral histories. Historians use primary sources to answer research questions and to gather evidence to inform their arguments.

This broadside announcement of the 1769 arrival of the ship Dembia to Charleston, South Carolina, describes a tragic historical event – the slave auction. It was created to inform local elites of the opportunity to bid on their fellow human beings. For historians, however, this text can also be used as evidence for a variety of scholarly questions, including inquiries about demographics, iconography, communications, capitalism, and gender.

This is only one example of how a single artifact, image, or document might be used to inform a broader argument or question. In the coming weeks we will present a variety of these unique materials selected from the collections of Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library

The RBML is Columbia University’s principal repository for primary source collections. The range of collections in RBML span more than 4,000 years and comprise rare printed works, cylinder seals, cuneiform tablets, papyri, and Coptic ostraca; medieval and renaissance manuscripts; as well as art and realia. Some 500,000 printed books and 14 miles of manuscripts, personal papers, and records form the core of the RBML holdings.

Key primary sources chosen from these collections by historians will complement the scholarly interpretations presented in the lectures and discussion forums. Tips for using these materials are available in the “Primary Sources” tab of the dropdown menu. Content-based modules using these sources will appear as part of the weekly sequences throughout the course.

Different types of texts offer varying potential questions and answers. Wills, financial records, and military accounts document the day-to-day functioning of a slave society. Photographic albums, engravings, and printed ephemera provide glimpses into the iconography of nineteenth-century culture. Personal belongings and correspondence beckon toward the intimate details of private lives, while mass-produced keepsakes blur the lines between historical evidence and pop-cultural kitsch. We will investigate the origins and intended functions of these materials. Placing individual documents in context will allow students the chance to think about the past in new ways. Asking scholarly questions of the materials will demonstrate how historians work to provide fresh interpretations of historical evidence

For scholars, these materials – and the questions they raise – constitute the foundational elements of historical work. Interrogating primary sources is one of the fundamental tasks every historian must perform in order to craft a nuanced, contingent, and evidence-based argument. The “Primary Sources” section of this course introduces students to that process

For further reading on the use of primary sources in historical research, students might consult these works:

Andrews, Thomas, and Flannery Burke. “What Does it Mean to Think Historically?” Perspectives on History (January 2007).

Barton, Keith C. “Primary Sources in History: Breaking Through the Myths.” Phi Delta Kappan 86 (June 2005).

Wineburg, Sam. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001

Week 1

A bill of sale recording the purchase of a slave, desertion lists from a Confederate army regiment, writing manuals used by freedmen and women to achieve literacy – these and other primary sources will be featured and examined throughout the course. Selected from the collections of Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library, these materials will complement the lectures and discussion forums to enrich our understanding of the United States in the Era of Civil War and Reconstruction.

What is a primary source?

A primary source is a document, image, or artifact that provides first-hand or eyewitness information about a particular historical person, event, or idea. Typical examples of primary sources include letters, diaries, newspapers, photographs, paintings, maps, and oral histories. Historians can use primary sources to answer research questions and to gather evidence to support their arguments.

Working with primary sources

When working with primary sources it is important to begin with a few observational and interpretive questions, which can often suggest future research directions.

- When was this source created? If the source is not dated, can you use any contextual clues to make an educated guess?

- Who created it? If no individual’s name is apparent, can you guess their position within society?

- What was the original purpose of this source? Why was it created and what was its intent?

- Who is the intended audience of the source? How does this influence the way information is presented?

- Is there anyone, besides the author, who is represented in the source? What can you learn about them?

- How has the meaning of the source changed over time?

- How might a historian use this source as a piece of evidence? What research questions might it help to answer? What story might you tell using this source?

Sample Exercise

Using the questions above to examine this Bill of Sale from the State of Louisiana might elicit the following types of answers: